In Short Unix / Linux Questions and Answers And Quick Guide

Unix Questions and Answers has been designed with a special intention of helping students and professionals preparing for various Certification Exams and Job Interviews. This section provides a useful collection of sample Interview Questions and Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs) and their answers with appropriate explanations.

| Sr.No. | Question/Answers Type | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unix Interview Questions This section provides a huge collection of Unix Interview Questions with their answers hidden in a box to challenge you to have a go at them before discovering the correct answer. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Unix Online Quiz This section provides a great collection of Unix Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs) on a single page along with their correct answers and explanation. If you select the right option, it turns green; else red. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Unix Online Test If you are preparing to appear for a Java and Unix Framework related certification exam, then this section is a must for you. This section simulates a real online test along with a given timer which challenges you to complete the test within a given time-frame. Finally you can check your overall test score and how you fared among millions of other candidates who attended this online test. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Unix Mock Test

This section provides various mock tests that you can download at

your local machine and solve offline. Every mock test is supplied with a

mock test key to let you verify the final score and grade yourself.Unix / Linux - Useful CommandThis quick guide lists commands, including a syntax and a brief description. For more detail, use −$man command Files and DirectoriesThese commands allow you to create directories and handle files.Manipulating dataThe contents of files can be compared and altered with the following commands.Compressed FilesFiles may be compressed to save space. Compressed files can be created and examined.

Getting InformationVarious Unix manuals and documentation are available on-line. The following Shell commands give information −

Network CommunicationThese following commands are used to send and receive files from a local Unix hosts to the remote host around the world.

Messages between UsersThe Unix systems support on-screen messages to other users and world-wide electronic mail −

Programming UtilitiesThe following programming tools and languages are available based on what you have installed on your Unix.Misc CommandsThese commands list or alter information about the system −Unix / Linux - Quick GuideUnix - Getting StartedWhat is Unix ?The Unix operating system is a set of programs that act as a link between the computer and the user.The computer programs that allocate the system resources and coordinate all the details of the computer's internals is called the operating system or the kernel. Users communicate with the kernel through a program known as the shell. The shell is a command line interpreter; it translates commands entered by the user and converts them into a language that is understood by the kernel.

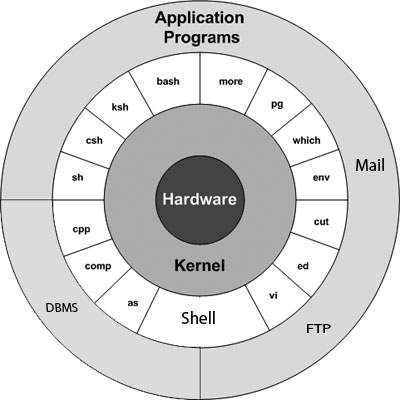

Unix ArchitectureHere is a basic block diagram of a Unix system − The main concept that unites all the versions of Unix is the following four basics −

The main concept that unites all the versions of Unix is the following four basics −

System BootupIf you have a computer which has the Unix operating system installed in it, then you simply need to turn on the system to make it live.As soon as you turn on the system, it starts booting up and finally it prompts you to log into the system, which is an activity to log into the system and use it for your day-to-day activities. Login UnixWhen you first connect to a Unix system, you usually see a prompt such as the following −login: To log in

login : amrood amrood's password: Last login: Sun Jun 14 09:32:32 2009 from 62.61.164.73 $You will be provided with a command prompt (sometime called the $ prompt ) where you type all your commands. For example, to check calendar, you need to type the cal command as follows − $ cal

June 2009

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 3 4 5 6

7 8 9 10 11 12 13

14 15 16 17 18 19 20

21 22 23 24 25 26 27

28 29 30

$

Change PasswordAll Unix systems require passwords to help ensure that your files and data remain your own and that the system itself is secure from hackers and crackers. Following are the steps to change your password −Step 1 − To start, type password at the command prompt as shown below. Step 2 − Enter your old password, the one you're currently using. Step 3 − Type in your new password. Always keep your password complex enough so that nobody can guess it. But make sure, you remember it. Step 4 − You must verify the password by typing it again. $ passwd Changing password for amrood (current) Unix password:****** New UNIX password:******* Retype new UNIX password:******* passwd: all authentication tokens updated successfully $Note − We have added asterisk (*) here just to show the location where you need to enter the current and new passwords otherwise at your system. It does not show you any character when you type. Listing Directories and FilesAll data in Unix is organized into files. All files are organized into directories. These directories are organized into a tree-like structure called the filesystem.You can use the ls command to list out all the files or directories available in a directory. Following is the example of using ls command with -l option. $ ls -l total 19621 drwxrwxr-x 2 amrood amrood 4096 Dec 25 09:59 uml -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 5341 Dec 25 08:38 uml.jpg drwxr-xr-x 2 amrood amrood 4096 Feb 15 2006 univ drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Dec 9 2007 urlspedia -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 276480 Dec 9 2007 urlspedia.tar drwxr-xr-x 8 root root 4096 Nov 25 2007 usr -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 3192 Nov 25 2007 webthumb.php -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 20480 Nov 25 2007 webthumb.tar -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 5654 Aug 9 2007 yourfile.mid -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 166255 Aug 9 2007 yourfile.swf $Here entries starting with d..... represent directories. For example, uml, univ and urlspedia are directories and rest of the entries are files. Who Are You?While you're logged into the system, you might be willing to know : Who am I?The easiest way to find out "who you are" is to enter the whoami command − $ whoami amrood $Try it on your system. This command lists the account name associated with the current login. You can try who am i command as well to get information about yourself. Who is Logged in?Sometime you might be interested to know who is logged in to the computer at the same time.There are three commands available to get you this information, based on how much you wish to know about the other users: users, who, and w. $ users amrood bablu qadir $ who amrood ttyp0 Oct 8 14:10 (limbo) bablu ttyp2 Oct 4 09:08 (calliope) qadir ttyp4 Oct 8 12:09 (dent) $Try the w command on your system to check the output. This lists down information associated with the users logged in the system. Logging OutWhen you finish your session, you need to log out of the system. This is to ensure that nobody else accesses your files.To log out

System ShutdownThe most consistent way to shut down a Unix system properly via the command line is to use one of the following commands −

Unix - File ManagementIn this chapter, we will discuss in detail about file management in Unix. All data in Unix is organized into files. All files are organized into directories. These directories are organized into a tree-like structure called the filesystem.When you work with Unix, one way or another, you spend most of your time working with files. This tutorial will help you understand how to create and remove files, copy and rename them, create links to them, etc. In Unix, there are three basic types of files −

Listing FilesTo list the files and directories stored in the current directory, use the following command −$lsHere is the sample output of the above command − $ls bin hosts lib res.03 ch07 hw1 pub test_results ch07.bak hw2 res.01 users docs hw3 res.02 workThe command ls supports the -l option which would help you to get more information about the listed files − $ls -l total 1962188 drwxrwxr-x 2 amrood amrood 4096 Dec 25 09:59 uml -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 5341 Dec 25 08:38 uml.jpg drwxr-xr-x 2 amrood amrood 4096 Feb 15 2006 univ drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Dec 9 2007 urlspedia -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 276480 Dec 9 2007 urlspedia.tar drwxr-xr-x 8 root root 4096 Nov 25 2007 usr drwxr-xr-x 2 200 300 4096 Nov 25 2007 webthumb-1.01 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 3192 Nov 25 2007 webthumb.php -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 20480 Nov 25 2007 webthumb.tar -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 5654 Aug 9 2007 yourfile.mid -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 166255 Aug 9 2007 yourfile.swf drwxr-xr-x 11 amrood amrood 4096 May 29 2007 zlib-1.2.3 $Here is the information about all the listed columns −

MetacharactersMetacharacters have a special meaning in Unix. For example, * and ? are metacharacters. We use * to match 0 or more characters, a question mark (?) matches with a single character.For Example − $ls ch*.docDisplays all the files, the names of which start with ch and end with .doc − ch01-1.doc ch010.doc ch02.doc ch03-2.doc ch04-1.doc ch040.doc ch05.doc ch06-2.doc ch01-2.doc ch02-1.doc cHere, * works as meta character which matches with any character. If you want to display all the files ending with just .doc, then you can use the following command − $ls *.doc Hidden FilesAn invisible file is one, the first character of which is the dot or the period character (.). Unix programs (including the shell) use most of these files to store configuration information.Some common examples of the hidden files include the files −

$ ls -a . .profile docs lib test_results .. .rhosts hosts pub users .emacs bin hw1 res.01 work .exrc ch07 hw2 res.02 .kshrc ch07.bak hw3 res.03 $

Creating FilesYou can use the vi editor to create ordinary files on any Unix system. You simply need to give the following command −$ vi filenameThe above command will open a file with the given filename. Now, press the key i to come into the edit mode. Once you are in the edit mode, you can start writing your content in the file as in the following program − This is unix file....I created it for the first time..... I'm going to save this content in this file.Once you are done with the program, follow these steps −

$ vi filename $ Editing FilesYou can edit an existing file using the vi editor. We will discuss in short how to open an existing file −$ vi filenameOnce the file is opened, you can come in the edit mode by pressing the key i and then you can proceed by editing the file. If you want to move here and there inside a file, then first you need to come out of the edit mode by pressing the key Esc. After this, you can use the following keys to move inside a file −

Display Content of a FileYou can use the cat command to see the content of a file. Following is a simple example to see the content of the above created file −$ cat filename This is unix file....I created it for the first time..... I'm going to save this content in this file. $You can display the line numbers by using the -b option along with the cat command as follows − $ cat -b filename 1 This is unix file....I created it for the first time..... 2 I'm going to save this content in this file. $ Counting Words in a FileYou can use the wc command to get a count of the total number of lines, words, and characters contained in a file. Following is a simple example to see the information about the file created above −$ wc filename 2 19 103 filename $Here is the detail of all the four columns −

$ wc filename1 filename2 filename3 Copying FilesTo make a copy of a file use the cp command. The basic syntax of the command is −$ cp source_file destination_fileFollowing is the example to create a copy of the existing file filename. $ cp filename copyfile $You will now find one more file copyfile in your current directory. This file will exactly be the same as the original file filename. Renaming FilesTo change the name of a file, use the mv command. Following is the basic syntax −$ mv old_file new_fileThe following program will rename the existing file filename to newfile. $ mv filename newfile $The mv command will move the existing file completely into the new file. In this case, you will find only newfile in your current directory. Deleting FilesTo delete an existing file, use the rm command. Following is the basic syntax −$ rm filenameCaution − A file may contain useful information. It is always recommended to be careful while using this Delete command. It is better to use the -i option along with rm command. Following is the example which shows how to completely remove the existing file filename. $ rm filename $You can remove multiple files at a time with the command given below − $ rm filename1 filename2 filename3 $ Standard Unix StreamsUnder normal circumstances, every Unix program has three streams (files) opened for it when it starts up −

Unix - Directory ManagementIn this chapter, we will discuss in detail about directory management in Unix.A directory is a file the solo job of which is to store the file names and the related information. All the files, whether ordinary, special, or directory, are contained in directories. Unix uses a hierarchical structure for organizing files and directories. This structure is often referred to as a directory tree. The tree has a single root node, the slash character (/), and all other directories are contained below it. Home DirectoryThe directory in which you find yourself when you first login is called your home directory.You will be doing much of your work in your home directory and subdirectories that you'll be creating to organize your files. You can go in your home directory anytime using the following command − $cd ~ $Here ~ indicates the home directory. Suppose you have to go in any other user's home directory, use the following command − $cd ~username $To go in your last directory, you can use the following command − $cd - $ Absolute/Relative PathnamesDirectories are arranged in a hierarchy with root (/) at the top. The position of any file within the hierarchy is described by its pathname.Elements of a pathname are separated by a /. A pathname is absolute, if it is described in relation to root, thus absolute pathnames always begin with a /. Following are some examples of absolute filenames. /etc/passwd /users/sjones/chem/notes /dev/rdsk/Os3A pathname can also be relative to your current working directory. Relative pathnames never begin with /. Relative to user amrood's home directory, some pathnames might look like this − chem/notes personal/resTo determine where you are within the filesystem hierarchy at any time, enter the command pwd to print the current working directory − $pwd /user0/home/amrood $ Listing DirectoriesTo list the files in a directory, you can use the following syntax −$ls dirnameFollowing is the example to list all the files contained in /usr/local directory − $ls /usr/local X11 bin gimp jikes sbin ace doc include lib share atalk etc info man ami Creating DirectoriesWe will now understand how to create directories. Directories are created by the following command −$mkdir dirnameHere, directory is the absolute or relative pathname of the directory you want to create. For example, the command − $mkdir mydir $Creates the directory mydir in the current directory. Here is another example − $mkdir /tmp/test-dir $This command creates the directory test-dir in the /tmp directory. The mkdir command produces no output if it successfully creates the requested directory. If you give more than one directory on the command line, mkdir creates each of the directories. For example, − $mkdir docs pub $Creates the directories docs and pub under the current directory. Creating Parent DirectoriesWe will now understand how to create parent directories. Sometimes when you want to create a directory, its parent directory or directories might not exist. In this case, mkdir issues an error message as follows −$mkdir /tmp/amrood/test mkdir: Failed to make directory "/tmp/amrood/test"; No such file or directory $In such cases, you can specify the -p option to the mkdir command. It creates all the necessary directories for you. For example − $mkdir -p /tmp/amrood/test $The above command creates all the required parent directories. Removing DirectoriesDirectories can be deleted using the rmdir command as follows −$rmdir dirname $Note − To remove a directory, make sure it is empty which means there should not be any file or sub-directory inside this directory. You can remove multiple directories at a time as follows − $rmdir dirname1 dirname2 dirname3 $The above command removes the directories dirname1, dirname2, and dirname3, if they are empty. The rmdir command produces no output if it is successful. Changing DirectoriesYou can use the cd command to do more than just change to a home directory. You can use it to change to any directory by specifying a valid absolute or relative path. The syntax is as given below −$cd dirname $Here, dirname is the name of the directory that you want to change to. For example, the command − $cd /usr/local/bin $Changes to the directory /usr/local/bin. From this directory, you can cd to the directory /usr/home/amrood using the following relative path − $cd ../../home/amrood $ Renaming DirectoriesThe mv (move) command can also be used to rename a directory. The syntax is as follows −$mv olddir newdir $You can rename a directory mydir to yourdir as follows − $mv mydir yourdir $ The directories . (dot) and .. (dot dot)The filename . (dot) represents the current working directory; and the filename .. (dot dot) represents the directory one level above the current working directory, often referred to as the parent directory.If we enter the command to show a listing of the current working directories/files and use the -a option to list all the files and the -l option to provide the long listing, we will receive the following result. $ls -la drwxrwxr-x 4 teacher class 2048 Jul 16 17.56 . drwxr-xr-x 60 root 1536 Jul 13 14:18 .. ---------- 1 teacher class 4210 May 1 08:27 .profile -rwxr-xr-x 1 teacher class 1948 May 12 13:42 memo $ Unix - File Permission / Access ModesIn this chapter, we will discuss in detail about file permission and access modes in Unix. File ownership is an important component of Unix that provides a secure method for storing files. Every file in Unix has the following attributes −

The Permission IndicatorsWhile using ls -l command, it displays various information related to file permission as follows −$ls -l /home/amrood -rwxr-xr-- 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 myfile drwxr-xr--- 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 mydirHere, the first column represents different access modes, i.e., the permission associated with a file or a directory. The permissions are broken into groups of threes, and each position in the group denotes a specific permission, in this order: read (r), write (w), execute (x) −

File Access ModesThe permissions of a file are the first line of defense in the security of a Unix system. The basic building blocks of Unix permissions are the read, write, and execute permissions, which have been described below −ReadGrants the capability to read, i.e., view the contents of the file.WriteGrants the capability to modify, or remove the content of the file.ExecuteUser with execute permissions can run a file as a program.Directory Access ModesDirectory access modes are listed and organized in the same manner as any other file. There are a few differences that need to be mentioned −ReadAccess to a directory means that the user can read the contents. The user can look at the filenames inside the directory.WriteAccess means that the user can add or delete files from the directory.ExecuteExecuting a directory doesn't really make sense, so think of this as a traverse permission.A user must have execute access to the bin directory in order to execute the ls or the cd command. Changing PermissionsTo change the file or the directory permissions, you use the chmod (change mode) command. There are two ways to use chmod — the symbolic mode and the absolute mode.Using chmod in Symbolic ModeThe easiest way for a beginner to modify file or directory permissions is to use the symbolic mode. With symbolic permissions you can add, delete, or specify the permission set you want by using the operators in the following table.

$ls -l testfile -rwxrwxr-- 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfileThen each example chmod command from the preceding table is run on the testfile, followed by ls –l, so you can see the permission changes − $chmod o+wx testfile $ls -l testfile -rwxrwxrwx 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfile $chmod u-x testfile $ls -l testfile -rw-rwxrwx 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfile $chmod g = rx testfile $ls -l testfile -rw-r-xrwx 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfileHere's how you can combine these commands on a single line − $chmod o+wx,u-x,g = rx testfile $ls -l testfile -rw-r-xrwx 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfile Using chmod with Absolute PermissionsThe second way to modify permissions with the chmod command is to use a number to specify each set of permissions for the file.Each permission is assigned a value, as the following table shows, and the total of each set of permissions provides a number for that set.

$ls -l testfile -rwxrwxr-- 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfileThen each example chmod command from the preceding table is run on the testfile, followed by ls –l, so you can see the permission changes − $ chmod 755 testfile $ls -l testfile -rwxr-xr-x 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfile $chmod 743 testfile $ls -l testfile -rwxr---wx 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfile $chmod 043 testfile $ls -l testfile ----r---wx 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfile Changing Owners and GroupsWhile creating an account on Unix, it assigns a owner ID and a group ID to each user. All the permissions mentioned above are also assigned based on the Owner and the Groups.Two commands are available to change the owner and the group of files −

Changing OwnershipThe chown command changes the ownership of a file. The basic syntax is as follows −$ chown user filelistThe value of the user can be either the name of a user on the system or the user id (uid) of a user on the system. The following example will help you understand the concept − $ chown amrood testfile $Changes the owner of the given file to the user amrood. NOTE − The super user, root, has the unrestricted capability to change the ownership of any file but normal users can change the ownership of only those files that they own. Changing Group OwnershipThe chgrp command changes the group ownership of a file. The basic syntax is as follows −$ chgrp group filelistThe value of group can be the name of a group on the system or the group ID (GID) of a group on the system. Following example helps you understand the concept − $ chgrp special testfile $Changes the group of the given file to special group. SUID and SGID File PermissionOften when a command is executed, it will have to be executed with special privileges in order to accomplish its task.As an example, when you change your password with the passwd command, your new password is stored in the file /etc/shadow. As a regular user, you do not have read or write access to this file for security reasons, but when you change your password, you need to have the write permission to this file. This means that the passwd program has to give you additional permissions so that you can write to the file /etc/shadow. Additional permissions are given to programs via a mechanism known as the Set User ID (SUID) and Set Group ID (SGID) bits. When you execute a program that has the SUID bit enabled, you inherit the permissions of that program's owner. Programs that do not have the SUID bit set are run with the permissions of the user who started the program. This is the case with SGID as well. Normally, programs execute with your group permissions, but instead your group will be changed just for this program to the group owner of the program. The SUID and SGID bits will appear as the letter "s" if the permission is available. The SUID "s" bit will be located in the permission bits where the owners’ execute permission normally resides. For example, the command − $ ls -l /usr/bin/passwd -r-sr-xr-x 1 root bin 19031 Feb 7 13:47 /usr/bin/passwd* $Shows that the SUID bit is set and that the command is owned by the root. A capital letter S in the execute position instead of a lowercase s indicates that the execute bit is not set. If the sticky bit is enabled on the directory, files can only be removed if you are one of the following users −

$ chmod ug+s dirname $ ls -l drwsr-sr-x 2 root root 4096 Jun 19 06:45 dirname $ Unix - EnvironmentIn this chapter, we will discuss in detail about the Unix environment. An important Unix concept is the environment, which is defined by environment variables. Some are set by the system, others by you, yet others by the shell, or any program that loads another program.A variable is a character string to which we assign a value. The value assigned could be a number, text, filename, device, or any other type of data. For example, first we set a variable TEST and then we access its value using the echo command − $TEST="Unix Programming" $echo $TESTIt produces the following result. Unix ProgrammingNote that the environment variables are set without using the $ sign but while accessing them we use the $ sign as prefix. These variables retain their values until we come out of the shell. When you log in to the system, the shell undergoes a phase called initialization to set up the environment. This is usually a two-step process that involves the shell reading the following files −

$This is the prompt where you can enter commands in order to have them executed. Note − The shell initialization process detailed here applies to all Bourne type shells, but some additional files are used by bash and ksh. The .profile FileThe file /etc/profile is maintained by the system administrator of your Unix machine and contains shell initialization information required by all users on a system.The file .profile is under your control. You can add as much shell customization information as you want to this file. The minimum set of information that you need to configure includes −

Setting the Terminal TypeUsually, the type of terminal you are using is automatically configured by either the login or getty programs. Sometimes, the auto configuration process guesses your terminal incorrectly.If your terminal is set incorrectly, the output of the commands might look strange, or you might not be able to interact with the shell properly. To make sure that this is not the case, most users set their terminal to the lowest common denominator in the following way − $TERM=vt100 $ Setting the PATHWhen you type any command on the command prompt, the shell has to locate the command before it can be executed.The PATH variable specifies the locations in which the shell should look for commands. Usually the Path variable is set as follows − $PATH=/bin:/usr/bin $Here, each of the individual entries separated by the colon character (:) are directories. If you request the shell to execute a command and it cannot find it in any of the directories given in the PATH variable, a message similar to the following appears − $hello hello: not found $There are variables like PS1 and PS2 which are discussed in the next section. PS1 and PS2 VariablesThe characters that the shell displays as your command prompt are stored in the variable PS1. You can change this variable to be anything you want. As soon as you change it, it'll be used by the shell from that point on.For example, if you issued the command − $PS1='=>' => => =>Your prompt will become =>. To set the value of PS1 so that it shows the working directory, issue the command − =>PS1="[\u@\h \w]\$" [root@ip-72-167-112-17 /var/www/tutorialspoint/unix]$ [root@ip-72-167-112-17 /var/www/tutorialspoint/unix]$The result of this command is that the prompt displays the user's username, the machine's name (hostname), and the working directory. There are quite a few escape sequences that can be used as value arguments for PS1; try to limit yourself to the most critical so that the prompt does not overwhelm you with information.

When you issue a command that is incomplete, the shell will display a secondary prompt and wait for you to complete the command and hit Enter again. The default secondary prompt is > (the greater than sign), but can be changed by re-defining the PS2 shell variable − Following is the example which uses the default secondary prompt − $ echo "this is a > test" this is a test $The example given below re-defines PS2 with a customized prompt − $ PS2="secondary prompt->" $ echo "this is a secondary prompt->test" this is a test $ Environment VariablesFollowing is the partial list of important environment variables. These variables are set and accessed as mentioned below −

$ echo $HOME /root ]$ echo $DISPLAY $ echo $TERM xterm $ echo $PATH /usr/local/bin:/bin:/usr/bin:/home/amrood/bin:/usr/local/bin $ Unix Basic Utilities - Printing, EmailIn this chapter, we will discuss in detail about Printing and Email as the basic utilities of Unix. So far, we have tried to understand the Unix OS and the nature of its basic commands. In this chapter, we will learn some important Unix utilities that can be used in our day-to-day life.Printing FilesBefore you print a file on a Unix system, you may want to reformat it to adjust the margins, highlight some words, and so on. Most files can also be printed without reformatting, but the raw printout may not be that appealing.Many versions of Unix include two powerful text formatters, nroff and troff. The pr CommandThe pr command does minor formatting of files on the terminal screen or for a printer. For example, if you have a long list of names in a file, you can format it onscreen into two or more columns.Following is the syntax for the pr command − pr option(s) filename(s)The pr changes the format of the file only on the screen or on the printed copy; it doesn't modify the original file. Following table lists some pr options −

$cat food Sweet Tooth Bangkok Wok Mandalay Afghani Cuisine Isle of Java Big Apple Deli Sushi and Sashimi Tio Pepe's Peppers ........ $Let's use the pr command to make a two-column report with the header Restaurants − $pr -2 -h "Restaurants" food Nov 7 9:58 1997 Restaurants Page 1 Sweet Tooth Isle of Java Bangkok Wok Big Apple Deli Mandalay Sushi and Sashimi Afghani Cuisine Tio Pepe's Peppers ........ $ The lp and lpr CommandsThe command lp or lpr prints a file onto paper as opposed to the screen display. Once you are ready with formatting using the pr command, you can use any of these commands to print your file on the printer connected to your computer.Your system administrator has probably set up a default printer at your site. To print a file named food on the default printer, use the lp or lpr command, as in the following example − $lp food request id is laserp-525 (1 file) $The lp command shows an ID that you can use to cancel the print job or check its status.

The lpstat and lpq CommandsThe lpstat command shows what's in the printer queue: request IDs, owners, file sizes, when the jobs were sent for printing, and the status of the requests.Use lpstat -o if you want to see all output requests other than just your own. Requests are shown in the order they'll be printed − $lpstat -o laserp-573 john 128865 Nov 7 11:27 on laserp laserp-574 grace 82744 Nov 7 11:28 laserp-575 john 23347 Nov 7 11:35 $The lpq gives slightly different information than lpstat -o − $lpq laserp is ready and printing Rank Owner Job Files Total Size active john 573 report.ps 128865 bytes 1st grace 574 ch03.ps ch04.ps 82744 bytes 2nd john 575 standard input 23347 bytes $Here the first line displays the printer status. If the printer is disabled or running out of paper, you may see different messages on this first line. The cancel and lprm CommandsThe cancel command terminates a printing request from the lp command. The lprm command terminates all lpr requests. You can specify either the ID of the request (displayed by lp or lpq) or the name of the printer.$cancel laserp-575 request "laserp-575" cancelled $To cancel whatever request is currently printing, regardless of its ID, simply enter cancel and the printer name − $cancel laserp request "laserp-573" cancelled $The lprm command will cancel the active job if it belongs to you. Otherwise, you can give job numbers as arguments, or use a dash (-) to remove all of your jobs − $lprm 575 dfA575diamond dequeued cfA575diamond dequeued $The lprm command tells you the actual filenames removed from the printer queue. Sending EmailYou use the Unix mail command to send and receive mail. Here is the syntax to send an email −$mail [-s subject] [-c cc-addr] [-b bcc-addr] to-addrHere are important options related to mail command −s

$mail -s "Test Message" admin@yahoo.comYou are then expected to type in your message, followed by "control-D" at the beginning of a line. To stop, simply type dot (.) as follows − Hi, This is a test . Cc:You can send a complete file using a redirect < operator as follows − $mail -s "Report 05/06/07" admin@yahoo.com < demo.txtTo check incoming email at your Unix system, you simply type email as follows − $mail no email Unix - Pipes and FiltersIn this chapter, we will discuss in detail about pipes and filters in Unix. You can connect two commands together so that the output from one program becomes the input of the next program. Two or more commands connected in this way form a pipe.To make a pipe, put a vertical bar (|) on the command line between two commands. When a program takes its input from another program, it performs some operation on that input, and writes the result to the standard output. It is referred to as a filter. The grep CommandThe grep command searches a file or files for lines that have a certain pattern. The syntax is −$grep pattern file(s)The name "grep" comes from the ed (a Unix line editor) command g/re/p which means “globally search for a regular expression and print all lines containing it”. A regular expression is either some plain text (a word, for example) and/or special characters used for pattern matching. The simplest use of grep is to look for a pattern consisting of a single word. It can be used in a pipe so that only those lines of the input files containing a given string are sent to the standard output. If you don't give grep a filename to read, it reads its standard input; that's the way all filter programs work − $ls -l | grep "Aug" -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 11008 Aug 6 14:10 ch02 -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 8515 Aug 6 15:30 ch07 -rw-rw-r-- 1 john doc 2488 Aug 15 10:51 intro -rw-rw-r-- 1 carol doc 1605 Aug 23 07:35 macros $There are various options which you can use along with the grep command −

Here, we are using the -i option to have case insensitive search − $ls -l | grep -i "carol.*aug" -rw-rw-r-- 1 carol doc 1605 Aug 23 07:35 macros $ The sort CommandThe sort command arranges lines of text alphabetically or numerically. The following example sorts the lines in the food file −$sort food Afghani Cuisine Bangkok Wok Big Apple Deli Isle of Java Mandalay Sushi and Sashimi Sweet Tooth Tio Pepe's Peppers $The sort command arranges lines of text alphabetically by default. There are many options that control the sorting −

The following pipe consists of the commands ls, grep, and sort − $ls -l | grep "Aug" | sort +4n -rw-rw-r-- 1 carol doc 1605 Aug 23 07:35 macros -rw-rw-r-- 1 john doc 2488 Aug 15 10:51 intro -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 8515 Aug 6 15:30 ch07 -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 11008 Aug 6 14:10 ch02 $This pipe sorts all files in your directory modified in August by the order of size, and prints them on the terminal screen. The sort option +4n skips four fields (fields are separated by blanks) then sorts the lines in numeric order. The pg and more CommandsA long output can normally be zipped by you on the screen, but if you run text through more or use the pg command as a filter; the display stops once the screen is full of text.Let's assume that you have a long directory listing. To make it easier to read the sorted listing, pipe the output through more as follows − $ls -l | grep "Aug" | sort +4n | more -rw-rw-r-- 1 carol doc 1605 Aug 23 07:35 macros -rw-rw-r-- 1 john doc 2488 Aug 15 10:51 intro -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 8515 Aug 6 15:30 ch07 -rw-rw-r-- 1 john doc 14827 Aug 9 12:40 ch03 . . . -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 16867 Aug 6 15:56 ch05 --More--(74%)The screen will fill up once the screen is full of text consisting of lines sorted by the order of the file size. At the bottom of the screen is the more prompt, where you can type a command to move through the sorted text. Once you're done with this screen, you can use any of the commands listed in the discussion of the more program. Unix - Processes ManagementIn this chapter, we will discuss in detail about process management in Unix. When you execute a program on your Unix system, the system creates a special environment for that program. This environment contains everything needed for the system to run the program as if no other program were running on the system.Whenever you issue a command in Unix, it creates, or starts, a new process. When you tried out the ls command to list the directory contents, you started a process. A process, in simple terms, is an instance of a running program. The operating system tracks processes through a five-digit ID number known as the pid or the process ID. Each process in the system has a unique pid. Pids eventually repeat because all the possible numbers are used up and the next pid rolls or starts over. At any point of time, no two processes with the same pid exist in the system because it is the pid that Unix uses to track each process. Starting a ProcessWhen you start a process (run a command), there are two ways you can run it −

Foreground ProcessesBy default, every process that you start runs in the foreground. It gets its input from the keyboard and sends its output to the screen.You can see this happen with the ls command. If you wish to list all the files in your current directory, you can use the following command − $ls ch*.docThis would display all the files, the names of which start with ch and end with .doc − ch01-1.doc ch010.doc ch02.doc ch03-2.doc ch04-1.doc ch040.doc ch05.doc ch06-2.doc ch01-2.doc ch02-1.docThe process runs in the foreground, the output is directed to my screen, and if the ls command wants any input (which it does not), it waits for it from the keyboard. While a program is running in the foreground and is time-consuming, no other commands can be run (start any other processes) because the prompt would not be available until the program finishes processing and comes out. Background ProcessesA background process runs without being connected to your keyboard. If the background process requires any keyboard input, it waits.The advantage of running a process in the background is that you can run other commands; you do not have to wait until it completes to start another! The simplest way to start a background process is to add an ampersand (&) at the end of the command. $ls ch*.doc &This displays all those files the names of which start with ch and end with .doc − ch01-1.doc ch010.doc ch02.doc ch03-2.doc ch04-1.doc ch040.doc ch05.doc ch06-2.doc ch01-2.doc ch02-1.docHere, if the ls command wants any input (which it does not), it goes into a stop state until we move it into the foreground and give it the data from the keyboard. That first line contains information about the background process - the job number and the process ID. You need to know the job number to manipulate it between the background and the foreground. Press the Enter key and you will see the following − [1] + Done ls ch*.doc & $The first line tells you that the ls command background process finishes successfully. The second is a prompt for another command. Listing Running ProcessesIt is easy to see your own processes by running the ps (process status) command as follows −$ps PID TTY TIME CMD 18358 ttyp3 00:00:00 sh 18361 ttyp3 00:01:31 abiword 18789 ttyp3 00:00:00 psOne of the most commonly used flags for ps is the -f ( f for full) option, which provides more information as shown in the following example − $ps -f UID PID PPID C STIME TTY TIME CMD amrood 6738 3662 0 10:23:03 pts/6 0:00 first_one amrood 6739 3662 0 10:22:54 pts/6 0:00 second_one amrood 3662 3657 0 08:10:53 pts/6 0:00 -ksh amrood 6892 3662 4 10:51:50 pts/6 0:00 ps -fHere is the description of all the fields displayed by ps -f command −

Stopping ProcessesEnding a process can be done in several different ways. Often, from a console-based command, sending a CTRL + C keystroke (the default interrupt character) will exit the command. This works when the process is running in the foreground mode.If a process is running in the background, you should get its Job ID using the ps command. After that, you can use the kill command to kill the process as follows − $ps -f UID PID PPID C STIME TTY TIME CMD amrood 6738 3662 0 10:23:03 pts/6 0:00 first_one amrood 6739 3662 0 10:22:54 pts/6 0:00 second_one amrood 3662 3657 0 08:10:53 pts/6 0:00 -ksh amrood 6892 3662 4 10:51:50 pts/6 0:00 ps -f $kill 6738 TerminatedHere, the kill command terminates the first_one process. If a process ignores a regular kill command, you can use kill -9 followed by the process ID as follows − $kill -9 6738 Terminated Parent and Child ProcessesEach unix process has two ID numbers assigned to it: The Process ID (pid) and the Parent process ID (ppid). Each user process in the system has a parent process.Most of the commands that you run have the shell as their parent. Check the ps -f example where this command listed both the process ID and the parent process ID. Zombie and Orphan ProcessesNormally, when a child process is killed, the parent process is updated via a SIGCHLD signal. Then the parent can do some other task or restart a new child as needed. However, sometimes the parent process is killed before its child is killed. In this case, the "parent of all processes," the init process, becomes the new PPID (parent process ID). In some cases, these processes are called orphan processes.When a process is killed, a ps listing may still show the process with a Z state. This is a zombie or defunct process. The process is dead and not being used. These processes are different from the orphan processes. They have completed execution but still find an entry in the process table. Daemon ProcessesDaemons are system-related background processes that often run with the permissions of root and services requests from other processes.A daemon has no controlling terminal. It cannot open /dev/tty. If you do a "ps -ef" and look at the tty field, all daemons will have a ? for the tty. To be precise, a daemon is a process that runs in the background, usually waiting for something to happen that it is capable of working with. For example, a printer daemon waiting for print commands. If you have a program that calls for lengthy processing, then it’s worth to make it a daemon and run it in the background. The top CommandThe top command is a very useful tool for quickly showing processes sorted by various criteria.It is an interactive diagnostic tool that updates frequently and shows information about physical and virtual memory, CPU usage, load averages, and your busy processes. Here is the simple syntax to run top command and to see the statistics of CPU utilization by different processes − $top Job ID Versus Process IDBackground and suspended processes are usually manipulated via job number (job ID). This number is different from the process ID and is used because it is shorter.In addition, a job can consist of multiple processes running in a series or at the same time, in parallel. Using the job ID is easier than tracking individual processes. Unix - Network Communication UtilitiesIn this chapter, we will discuss in detail about network communication utilities in Unix. When you work in a distributed environment, you need to communicate with remote users and you also need to access remote Unix machines.There are several Unix utilities that help users compute in a networked, distributed environment. This chapter lists a few of them. The ping UtilityThe ping command sends an echo request to a host available on the network. Using this command, you can check if your remote host is responding well or not.The ping command is useful for the following −

SyntaxFollowing is the simple syntax to use the ping command −$ping hostname or ip-addressThe above command starts printing a response after every second. To come out of the command, you can terminate it by pressing CNTRL + C keys. ExampleFollowing is an example to check the availability of a host available on the network −$ping google.com PING google.com (74.125.67.100) 56(84) bytes of data. 64 bytes from 74.125.67.100: icmp_seq = 1 ttl = 54 time = 39.4 ms 64 bytes from 74.125.67.100: icmp_seq = 2 ttl = 54 time = 39.9 ms 64 bytes from 74.125.67.100: icmp_seq = 3 ttl = 54 time = 39.3 ms 64 bytes from 74.125.67.100: icmp_seq = 4 ttl = 54 time = 39.1 ms 64 bytes from 74.125.67.100: icmp_seq = 5 ttl = 54 time = 38.8 ms --- google.com ping statistics --- 22 packets transmitted, 22 received, 0% packet loss, time 21017ms rtt min/avg/max/mdev = 38.867/39.334/39.900/0.396 ms $If a host does not exist, you will receive the following output − $ping giiiiiigle.com ping: unknown host giiiiigle.com $ The ftp UtilityHere, ftp stands for File Transfer Protocol. This utility helps you upload and download your file from one computer to another computer.The ftp utility has its own set of Unix-like commands. These commands help you perform tasks such as −

SyntaxFollowing is the simple syntax to use the ping command −$ftp hostname or ip-addressThe above command would prompt you for the login ID and the password. Once you are authenticated, you can access the home directory of the login account and you would be able to perform various commands. The following tables lists out a few important commands −

ExampleFollowing is the example to show the working of a few commands −$ftp amrood.com Connected to amrood.com. 220 amrood.com FTP server (Ver 4.9 Thu Sep 2 20:35:07 CDT 2009) Name (amrood.com:amrood): amrood 331 Password required for amrood. Password: 230 User amrood logged in. ftp> dir 200 PORT command successful. 150 Opening data connection for /bin/ls. total 1464 drwxr-sr-x 3 amrood group 1024 Mar 11 20:04 Mail drwxr-sr-x 2 amrood group 1536 Mar 3 18:07 Misc drwxr-sr-x 5 amrood group 512 Dec 7 10:59 OldStuff drwxr-sr-x 2 amrood group 1024 Mar 11 15:24 bin drwxr-sr-x 5 amrood group 3072 Mar 13 16:10 mpl -rw-r--r-- 1 amrood group 209671 Mar 15 10:57 myfile.out drwxr-sr-x 3 amrood group 512 Jan 5 13:32 public drwxr-sr-x 3 amrood group 512 Feb 10 10:17 pvm3 226 Transfer complete. ftp> cd mpl 250 CWD command successful. ftp> dir 200 PORT command successful. 150 Opening data connection for /bin/ls. total 7320 -rw-r--r-- 1 amrood group 1630 Aug 8 1994 dboard.f -rw-r----- 1 amrood group 4340 Jul 17 1994 vttest.c -rwxr-xr-x 1 amrood group 525574 Feb 15 11:52 wave_shift -rw-r--r-- 1 amrood group 1648 Aug 5 1994 wide.list -rwxr-xr-x 1 amrood group 4019 Feb 14 16:26 fix.c 226 Transfer complete. ftp> get wave_shift 200 PORT command successful. 150 Opening data connection for wave_shift (525574 bytes). 226 Transfer complete. 528454 bytes received in 1.296 seconds (398.1 Kbytes/s) ftp> quit 221 Goodbye. $ The telnet UtilityThere are times when we are required to connect to a remote Unix machine and work on that machine remotely. Telnet is a utility that allows a computer user at one site to make a connection, login and then conduct work on a computer at another site.Once you login using Telnet, you can perform all the activities on your remotely connected machine. The following is an example of Telnet session − C:>telnet amrood.com

Trying...

Connected to amrood.com.

Escape character is '^]'.

login: amrood

amrood's Password:

*****************************************************

* *

* *

* WELCOME TO AMROOD.COM *

* *

* *

*****************************************************

Last unsuccessful login: Fri Mar 3 12:01:09 IST 2009

Last login: Wed Mar 8 18:33:27 IST 2009 on pts/10

{ do your work }

$ logout

Connection closed.

C:>

The finger UtilityThe finger command displays information about users on a given host. The host can be either local or remote.Finger may be disabled on other systems for security reasons. Following is the simple syntax to use the finger command − Check all the logged-in users on the local machine − $ finger Login Name Tty Idle Login Time Office amrood pts/0 Jun 25 08:03 (62.61.164.115)Get information about a specific user available on the local machine − $ finger amrood Login: amrood Name: (null) Directory: /home/amrood Shell: /bin/bash On since Thu Jun 25 08:03 (MST) on pts/0 from 62.61.164.115 No mail. No Plan.Check all the logged-in users on the remote machine − $ finger @avtar.com Login Name Tty Idle Login Time Office amrood pts/0 Jun 25 08:03 (62.61.164.115)Get the information about a specific user available on the remote machine − $ finger amrood@avtar.com Login: amrood Name: (null) Directory: /home/amrood Shell: /bin/bash On since Thu Jun 25 08:03 (MST) on pts/0 from 62.61.164.115 No mail. No Plan. Unix - The vi Editor TutorialIn this chapter, we will understand how the vi Editor works in Unix. There are many ways to edit files in Unix. Editing files using the screen-oriented text editor vi is one of the best ways. This editor enables you to edit lines in context with other lines in the file.An improved version of the vi editor which is called the VIM has also been made available now. Here, VIM stands for Vi IMproved. vi is generally considered the de facto standard in Unix editors because −

Starting the vi EditorThe following table lists out the basic commands to use the vi editor −

$vi testfileThe above command will generate the following output − | ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ "testfile" [New File]You will notice a tilde (~) on each line following the cursor. A tilde represents an unused line. If a line does not begin with a tilde and appears to be blank, there is a space, tab, newline, or some other non-viewable character present. You now have one open file to start working on. Before proceeding further, let us understand a few important concepts. Operation ModesWhile working with the vi editor, we usually come across the following two modes −

Hint − If you are not sure which mode you are in, press the Esc key twice; this will take you to the command mode. You open a file using the vi editor. Start by typing some characters and then come to the command mode to understand the difference. Getting Out of viThe command to quit out of vi is :q. Once in the command mode, type colon, and 'q', followed by return. If your file has been modified in any way, the editor will warn you of this, and not let you quit. To ignore this message, the command to quit out of vi without saving is :q!. This lets you exit vi without saving any of the changes.The command to save the contents of the editor is :w. You can combine the above command with the quit command, or use :wq and return. The easiest way to save your changes and exit vi is with the ZZ command. When you are in the command mode, type ZZ. The ZZ command works the same way as the :wq command. If you want to specify/state any particular name for the file, you can do so by specifying it after the :w. For example, if you wanted to save the file you were working on as another filename called filename2, you would type :w filename2 and return. Moving within a FileTo move around within a file without affecting your text, you must be in the command mode (press Esc twice). The following table lists out a few commands you can use to move around one character at a time −

Control CommandsThe following commands can be used with the Control Key to performs functions as given in the table below −Editing FilesTo edit the file, you need to be in the insert mode. There are many ways to enter the insert mode from the command mode −

Deleting CharactersHere is a list of important commands, which can be used to delete characters and lines in an open file −

It is recommended that the commands are practiced before we proceed further. Change CommandsYou also have the capability to change characters, words, or lines in vi without deleting them. Here are the relevant commands −

Copy and Paste CommandsYou can copy lines or words from one place and then you can paste them at another place using the following commands −

Advanced CommandsThere are some advanced commands that simplify day-to-day editing and allow for more efficient use of vi −Word and Character SearchingThe vi editor has two kinds of searches: string and character. For a string search, the / and ? commands are used. When you start these commands, the command just typed will be shown on the last line of the screen, where you type the particular string to look for.These two commands differ only in the direction where the search takes place −

The t and T commands search for a character on the current line only, but for t, the cursor moves to the position before the character, and T searches the line backwards to the position after the character. Set CommandsYou can change the look and feel of your vi screen using the following :set commands. Once you are in the command mode, type :set followed by any of the following commands.

Running CommandsThe vi has the capability to run commands from within the editor. To run a command, you only need to go to the command mode and type :! command.For example, if you want to check whether a file exists before you try to save your file with that filename, you can type :! ls and you will see the output of ls on the screen. You can press any key (or the command's escape sequence) to return to your vi session. Replacing TextThe substitution command (:s/) enables you to quickly replace words or groups of words within your files. Following is the syntax to replace text −:s/search/replace/gThe g stands for globally. The result of this command is that all occurrences on the cursor's line are changed. Important Points to NoteThe following points will add to your success with vi −

Unix - What is Shells?A Shell provides you with an interface to the Unix system. It gathers input from you and executes programs based on that input. When a program finishes executing, it displays that program's output.Shell is an environment in which we can run our commands, programs, and shell scripts. There are different flavors of a shell, just as there are different flavors of operating systems. Each flavor of shell has its own set of recognized commands and functions. Shell PromptThe prompt, $, which is called the command prompt, is issued by the shell. While the prompt is displayed, you can type a command.Shell reads your input after you press Enter. It determines the command you want executed by looking at the first word of your input. A word is an unbroken set of characters. Spaces and tabs separate words. Following is a simple example of the date command, which displays the current date and time − $date Thu Jun 25 08:30:19 MST 2009You can customize your command prompt using the environment variable PS1 explained in the Environment tutorial. Shell TypesIn Unix, there are two major types of shells −

Bourne shell was the first shell to appear on Unix systems, thus it is referred to as "the shell". Bourne shell is usually installed as /bin/sh on most versions of Unix. For this reason, it is the shell of choice for writing scripts that can be used on different versions of Unix. In this chapter, we are going to cover most of the Shell concepts that are based on the Borne Shell. Shell ScriptsThe basic concept of a shell script is a list of commands, which are listed in the order of execution. A good shell script will have comments, preceded by # sign, describing the steps.There are conditional tests, such as value A is greater than value B, loops allowing us to go through massive amounts of data, files to read and store data, and variables to read and store data, and the script may include functions. We are going to write many scripts in the next sections. It would be a simple text file in which we would put all our commands and several other required constructs that tell the shell environment what to do and when to do it. Shell scripts and functions are both interpreted. This means they are not compiled. Example ScriptAssume we create a test.sh script. Note all the scripts would have the .sh extension. Before you add anything else to your script, you need to alert the system that a shell script is being started. This is done using the shebang construct. For example −#!/bin/shThis tells the system that the commands that follow are to be executed by the Bourne shell. It's called a shebang because the # symbol is called a hash, and the ! symbol is called a bang. To create a script containing these commands, you put the shebang line first and then add the commands − #!/bin/bash pwd ls Shell CommentsYou can put your comments in your script as follows −#!/bin/bash # Author : Zara Ali # Copyright (c) Tutorialspoint.com # Script follows here: pwd lsSave the above content and make the script executable − $chmod +x test.shThe shell script is now ready to be executed − $./test.shUpon execution, you will receive the following result − /home/amrood index.htm unix-basic_utilities.htm unix-directories.htm test.sh unix-communication.htm unix-environment.htmNote − To execute a program available in the current directory, use ./program_name Extended Shell ScriptsShell scripts have several required constructs that tell the shell environment what to do and when to do it. Of course, most scripts are more complex than the above one.The shell is, after all, a real programming language, complete with variables, control structures, and so forth. No matter how complicated a script gets, it is still just a list of commands executed sequentially. The following script uses the read command which takes the input from the keyboard and assigns it as the value of the variable PERSON and finally prints it on STDOUT. #!/bin/sh # Author : Zara Ali # Copyright (c) Tutorialspoint.com # Script follows here: echo "What is your name?" read PERSON echo "Hello, $PERSON"Here is a sample run of the script − $./test.sh What is your name? Zara Ali Hello, Zara Ali $ Unix - Using Shell VariablesIn this chapter, we will learn how to use Shell variables in Unix. A variable is a character string to which we assign a value. The value assigned could be a number, text, filename, device, or any other type of data.A variable is nothing more than a pointer to the actual data. The shell enables you to create, assign, and delete variables. Variable NamesThe name of a variable can contain only letters (a to z or A to Z), numbers ( 0 to 9) or the underscore character ( _).By convention, Unix shell variables will have their names in UPPERCASE. The following examples are valid variable names − _ALI TOKEN_A VAR_1 VAR_2Following are the examples of invalid variable names − 2_VAR -VARIABLE VAR1-VAR2 VAR_A!The reason you cannot use other characters such as !, *, or - is that these characters have a special meaning for the shell. Defining VariablesVariables are defined as follows −variable_name=variable_valueFor example − NAME="Zara Ali"The above example defines the variable NAME and assigns the value "Zara Ali" to it. Variables of this type are called scalar variables. A scalar variable can hold only one value at a time. Shell enables you to store any value you want in a variable. For example − VAR1="Zara Ali" VAR2=100 Accessing ValuesTo access the value stored in a variable, prefix its name with the dollar sign ($) −For example, the following script will access the value of defined variable NAME and print it on STDOUT − Live Demo #!/bin/sh NAME="Zara Ali" echo $NAMEThe above script will produce the following value − Zara Ali Read-only VariablesShell provides a way to mark variables as read-only by using the read-only command. After a variable is marked read-only, its value cannot be changed.For example, the following script generates an error while trying to change the value of NAME − Live Demo #!/bin/sh NAME="Zara Ali" readonly NAME NAME="Qadiri"The above script will generate the following result − /bin/sh: NAME: This variable is read only. Unsetting VariablesUnsetting or deleting a variable directs the shell to remove the variable from the list of variables that it tracks. Once you unset a variable, you cannot access the stored value in the variable.Following is the syntax to unset a defined variable using the unset command − unset variable_nameThe above command unsets the value of a defined variable. Here is a simple example that demonstrates how the command works − #!/bin/sh NAME="Zara Ali" unset NAME echo $NAMEThe above example does not print anything. You cannot use the unset command to unset variables that are marked readonly. Variable TypesWhen a shell is running, three main types of variables are present −

Unix - Special VariablesIn this chapter, we will discuss in detail about special variable in Unix. In one of our previous chapters, we understood how to be careful when we use certain nonalphanumeric characters in variable names. This is because those characters are used in the names of special Unix variables. These variables are reserved for specific functions.For example, the $ character represents the process ID number, or PID, of the current shell − $echo $$

The above command writes the PID of the current shell −29949The following table shows a number of special variables that you can use in your shell scripts −

Command-Line ArgumentsThe command-line arguments $1, $2, $3, ...$9 are positional parameters, with $0 pointing to the actual command, program, shell script, or function and $1, $2, $3, ...$9 as the arguments to the command.Following script uses various special variables related to the command line − #!/bin/sh echo "File Name: $0" echo "First Parameter : $1" echo "Second Parameter : $2" echo "Quoted Values: $@" echo "Quoted Values: $*" echo "Total Number of Parameters : $#"Here is a sample run for the above script − $./test.sh Zara Ali File Name : ./test.sh First Parameter : Zara Second Parameter : Ali Quoted Values: Zara Ali Quoted Values: Zara Ali Total Number of Parameters : 2 Special Parameters $* and $@There are special parameters that allow accessing all the command-line arguments at once. $* and $@ both will act the same unless they are enclosed in double quotes, "".Both the parameters specify the command-line arguments. However, the "$*" special parameter takes the entire list as one argument with spaces between and the "$@" special parameter takes the entire list and separates it into separate arguments. We can write the shell script as shown below to process an unknown number of commandline arguments with either the $* or $@ special parameters − #!/bin/sh for TOKEN in $* do echo $TOKEN doneHere is a sample run for the above script − $./test.sh Zara Ali 10 Years Old Zara Ali 10 Years OldNote − Here do...done is a kind of loop that will be covered in a subsequent tutorial. Exit StatusThe $? variable represents the exit status of the previous command.Exit status is a numerical value returned by every command upon its completion. As a rule, most commands return an exit status of 0 if they were successful, and 1 if they were unsuccessful. Some commands return additional exit statuses for particular reasons. For example, some commands differentiate between kinds of errors and will return various exit values depending on the specific type of failure. Following is the example of successful command − $./test.sh Zara Ali File Name : ./test.sh First Parameter : Zara Second Parameter : Ali Quoted Values: Zara Ali Quoted Values: Zara Ali Total Number of Parameters : 2 $echo $? 0 $ Unix - Using Shell ArraysIn this chapter, we will discuss how to use shell arrays in Unix. A shell variable is capable enough to hold a single value. These variables are called scalar variables.Shell supports a different type of variable called an array variable. This can hold multiple values at the same time. Arrays provide a method of grouping a set of variables. Instead of creating a new name for each variable that is required, you can use a single array variable that stores all the other variables. All the naming rules discussed for Shell Variables would be applicable while naming arrays. Defining Array ValuesThe difference between an array variable and a scalar variable can be explained as follows.Suppose you are trying to represent the names of various students as a set of variables. Each of the individual variables is a scalar variable as follows − NAME01="Zara" NAME02="Qadir" NAME03="Mahnaz" NAME04="Ayan" NAME05="Daisy"We can use a single array to store all the above mentioned names. Following is the simplest method of creating an array variable. This helps assign a value to one of its indices. array_name[index]=valueHere array_name is the name of the array, index is the index of the item in the array that you want to set, and value is the value you want to set for that item. As an example, the following commands − NAME[0]="Zara" NAME[1]="Qadir" NAME[2]="Mahnaz" NAME[3]="Ayan" NAME[4]="Daisy"If you are using the ksh shell, here is the syntax of array initialization − set -A array_name value1 value2 ... valuenIf you are using the bash shell, here is the syntax of array initialization − array_name=(value1 ... valuen) Accessing Array ValuesAfter you have set any array variable, you access it as follows −${array_name[index]}

Here array_name is the name of the array, and index is the index of the value to be accessed. Following is an example to understand the concept −Live Demo #!/bin/sh NAME[0]="Zara" NAME[1]="Qadir" NAME[2]="Mahnaz" NAME[3]="Ayan" NAME[4]="Daisy" echo "First Index: ${NAME[0]}" echo "Second Index: ${NAME[1]}"The above example will generate the following result − $./test.sh First Index: Zara Second Index: QadirYou can access all the items in an array in one of the following ways − ${array_name[*]}

${array_name[@]}

Here array_name is the name of the array you are interested in. Following example will help you understand the concept −Live Demo #!/bin/sh NAME[0]="Zara" NAME[1]="Qadir" NAME[2]="Mahnaz" NAME[3]="Ayan" NAME[4]="Daisy" echo "First Method: ${NAME[*]}" echo "Second Method: ${NAME[@]}"The above example will generate the following result − $./test.sh First Method: Zara Qadir Mahnaz Ayan Daisy Second Method: Zara Qadir Mahnaz Ayan Daisy Unix - Shell Basic OperatorsThere are various operators supported by each shell. We will discuss in detail about Bourne shell (default shell) in this chapter.We will now discuss the following operators −

The following example shows how to add two numbers − Live Demo #!/bin/sh val=`expr 2 + 2` echo "Total value : $val"The above script will generate the following result − Total value : 4The following points need to be considered while adding −

Arithmetic OperatorsThe following arithmetic operators are supported by Bourne Shell.Assume variable a holds 10 and variable b holds 20 then − Show Examples

All the arithmetical calculations are done using long integers. Relational OperatorsBourne Shell supports the following relational operators that are specific to numeric values. These operators do not work for string values unless their value is numeric.For example, following operators will work to check a relation between 10 and 20 as well as in between "10" and "20" but not in between "ten" and "twenty". Assume variable a holds 10 and variable b holds 20 then − Show Examples

Boolean OperatorsThe following Boolean operators are supported by the Bourne Shell.Assume variable a holds 10 and variable b holds 20 then − Show Examples

String OperatorsThe following string operators are supported by Bourne Shell.Assume variable a holds "abc" and variable b holds "efg" then − Show Examples

File Test OperatorsWe have a few operators that can be used to test various properties associated with a Unix file.Assume a variable file holds an existing file name "test" the size of which is 100 bytes and has read, write and execute permission on − Show Examples

C Shell OperatorsFollowing link will give you a brief idea on C Shell Operators −C Shell Operators Korn Shell OperatorsFollowing link helps you understand Korn Shell Operators −Korn Shell Operators Unix - Shell Decision MakingIn this chapter, we will understand shell decision-making in Unix. While writing a shell script, there may be a situation when you need to adopt one path out of the given two paths. So you need to make use of conditional statements that allow your program to make correct decisions and perform the right actions.Unix Shell supports conditional statements which are used to perform different actions based on different conditions. We will now understand two decision-making statements here −