UNIX / LINUX Tutorial Basics

Unix / Linux for Beginners

Unix is a computer Operating System which is capable of handling activities from multiple users at the same time. The development of Unix started around 1969 at AT&T Bell Labs by Ken Thompson

and Dennis Ritchie. This tutorial gives a very good understanding on Unix.

Basics:

Unix is a computer Operating System which is capable of handling activities from multiple users at the same time. The development of Unix started around 1969 at AT&T Bell Labs by Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie. This tutorial gives a very good understanding on Unix.

We assume you have adequate exposure to Operating Systems and their functionalities. A basic understanding on various computer concepts will also help you in understanding the various exercises given in this tutorial.

If you are willing to learn the Unix/Linux basic commands and Shell script but you do not have a setup for the same, then do not worry — The CodingGround is available on a highend dedicated server giving you real programming experience with the comfort of singleclick execution. Yes! It is absolutely free and online.

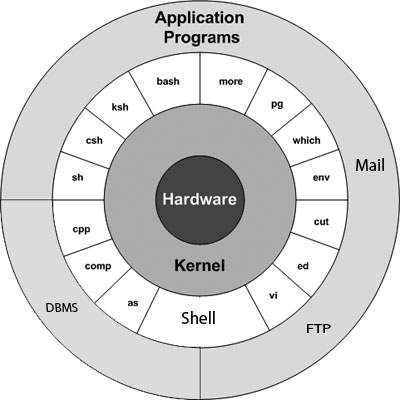

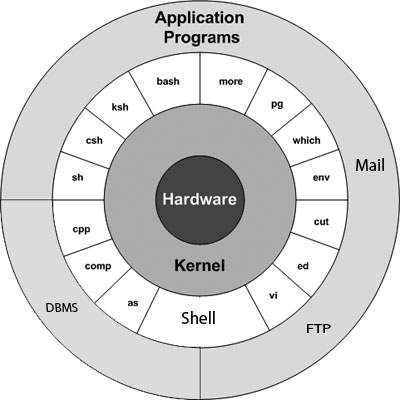

The computer programs that allocate the system resources and coordinate all the details of the computer's internals is called the operating system or the kernel.

Users communicate with the kernel through a program known as the shell. The shell is a command line interpreter; it translates commands entered by the user and converts them into a language that is understood by the kernel.

The main concept that unites all the versions of Unix is the following four basics −

The main concept that unites all the versions of Unix is the following four basics −

As soon as you turn on the system, it starts booting up and finally it prompts you to log into the system, which is an activity to log into the system and use it for your day-to-day activities.

Step 1 − To start, type password at the command prompt as shown below.

Step 2 − Enter your old password, the one you're currently using.

Step 3 − Type in your new password. Always keep your password complex enough so that nobody can guess it. But make sure, you remember it.

Step 4 − You must verify the password by typing it again.

You can use the ls command to list out all the files or directories available in a directory. Following is the example of using ls command with -l option.

The easiest way to find out "who you are" is to enter the whoami command −

There are three commands available to get you this information, based on how much you wish to know about the other users: users, who, and w.

To log out

You typically need to be the super user or root (the most privileged

account on a Unix system) to shut down the system. However, on some

standalone or personally-owned Unix boxes, an administrative user and

sometimes regular users can do so.

File Management

In this chapter, we will discuss in detail about file management in Unix. All data in Unix is organized into files. All files are organized into directories. These directories are organized into a tree-like structure called the filesystem.

When you work with Unix, one way or another, you spend most of your time working with files. This tutorial will help you understand how to create and remove files, copy and rename them, create links to them, etc.

In Unix, there are three basic types of files −

For Example −

Some common examples of the hidden files include the files −

Following is the example which shows how to completely remove the existing file filename.

The permissions are broken into groups of threes, and each position in the group denotes a specific permission, in this order: read (r), write (w), execute (x) −

A user must have execute access to the bin directory in order to execute the ls or the cd command.

Here's an example using testfile. Running ls -1 on the testfile shows that the file's permissions are as follows −

Each permission is assigned a value, as the following table shows, and the total of each set of permissions provides a number for that set.

Here's an example using the testfile. Running ls -1 on the testfile shows that the file's permissions are as follows −

Two commands are available to change the owner and the group of files −

The following example will help you understand the concept −

NOTE − The super user, root, has the unrestricted capability to change the ownership of any file but normal users can change the ownership of only those files that they own.

Following example helps you understand the concept −

As an example, when you change your password with the passwd command, your new password is stored in the file /etc/shadow.

As a regular user, you do not have read or write access to this file for security reasons, but when you change your password, you need to have the write permission to this file. This means that the passwd program has to give you additional permissions so that you can write to the file /etc/shadow.

Additional permissions are given to programs via a mechanism known as the Set User ID (SUID) and Set Group ID (SGID) bits.

When you execute a program that has the SUID bit enabled, you inherit the permissions of that program's owner. Programs that do not have the SUID bit set are run with the permissions of the user who started the program.

This is the case with SGID as well. Normally, programs execute with your group permissions, but instead your group will be changed just for this program to the group owner of the program.

The SUID and SGID bits will appear as the letter "s" if the permission is available. The SUID "s" bit will be located in the permission bits where the owners’ execute permission normally resides.

For example, the command −

If the sticky bit is enabled on the directory, files can only be removed if you are one of the following users −

For example, first we set a variable TEST and then we access its value using the echo command −

$TEST="Unix Programming" $echo $TEST It produces the following result.

Unix Programming Note that the environment variables are set without using the $ sign but while accessing them we use the $ sign as prefix. These variables retain their values until we come out of the shell.

When you log in to the system, the shell undergoes a phase called initialization to set up the environment. This is usually a two-step process that involves the shell reading the following files −

$ This is the prompt where you can enter commands in order to have them executed.

Note − The shell initialization process detailed here applies to all Bourne type shells, but some additional files are used by bash and ksh.

The file .profile is under your control. You can add as much shell customization information as you want to this file. The minimum set of information that you need to configure includes −

If your terminal is set incorrectly, the output of the commands might look strange, or you might not be able to interact with the shell properly.

To make sure that this is not the case, most users set their terminal to the lowest common denominator in the following way −

$TERM=vt100 $

The PATH variable specifies the locations in which the shell should look for commands. Usually the Path variable is set as follows −

$PATH=/bin:/usr/bin $ Here, each of the individual entries separated by the colon character (:) are directories. If you request the shell to execute a command and it cannot find it in any of the directories given in the PATH variable, a message similar to the following appears −

$hello hello: not found $ There are variables like PS1 and PS2 which are discussed in the next section.

For example, if you issued the command −

$PS1='=>' => => => Your prompt will become =>. To set the value of PS1 so that it shows the working directory, issue the command −

=>PS1="[\u@\h \w]\$" [root@ip-72-167-112-17 /var/www/tutorialspoint/unix]$ [root@ip-72-167-112-17 /var/www/tutorialspoint/unix]$ The result of this command is that the prompt displays the user's username, the machine's name (hostname), and the working directory.

There are quite a few escape sequences that can be used as value arguments for PS1; try to limit yourself to the most critical so that the prompt does not overwhelm you with information.

You can make the change yourself every time you log in, or you can

have the change made automatically in PS1 by adding it to your .profile file.

When you issue a command that is incomplete, the shell will display a secondary prompt and wait for you to complete the command and hit Enter again.

The default secondary prompt is > (the greater than sign), but can be changed by re-defining the PS2 shell variable −

Following is the example which uses the default secondary prompt −

$ echo "this is a > test" this is a test $ The example given below re-defines PS2 with a customized prompt −

$ PS2="secondary prompt->" $ echo "this is a secondary prompt->test" this is a test $

Following is the sample example showing few environment variables −

$ echo $HOME /root ]$ echo $DISPLAY $ echo $TERM xterm $ echo $PATH /usr/local/bin:/bin:/usr/bin:/home/amrood/bin:/usr/local/bin $

Many versions of Unix include two powerful text formatters, nroff and troff.

Following is the syntax for the pr command −

Before using pr, here are the contents of a sample file named food.

Your system administrator has probably set up a default printer at your site. To print a file named food on the default printer, use the lp or lpr command, as in the following example −

Use lpstat -o if you want to see all output requests other than just your own. Requests are shown in the order they'll be printed −

Following is an example to send a test message to admin@yahoo.com.

When a program takes its input from another program, it performs some operation on that input, and writes the result to the standard output. It is referred to as a filter.

$grep pattern file(s) The name "grep" comes from the ed (a Unix line editor) command g/re/p which means “globally search for a regular expression and print all lines containing it”.

A regular expression is either some plain text (a word, for example) and/or special characters used for pattern matching.

The simplest use of grep is to look for a pattern consisting of a single word. It can be used in a pipe so that only those lines of the input files containing a given string are sent to the standard output. If you don't give grep a filename to read, it reads its standard input; that's the way all filter programs work −

$ls -l | grep "Aug" -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 11008 Aug 6 14:10 ch02 -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 8515 Aug 6 15:30 ch07 -rw-rw-r-- 1 john doc 2488 Aug 15 10:51 intro -rw-rw-r-- 1 carol doc 1605 Aug 23 07:35 macros $ There are various options which you can use along with the grep command −

Let us now use a regular expression that tells grep to find lines with "carol", followed by zero or other characters abbreviated in a regular expression as ".*"), then followed by "Aug".−

Here, we are using the -i option to have case insensitive search −

$ls -l | grep -i "carol.*aug" -rw-rw-r-- 1 carol doc 1605 Aug 23 07:35 macros $

$sort food Afghani Cuisine Bangkok Wok Big Apple Deli Isle of Java Mandalay Sushi and Sashimi Sweet Tooth Tio Pepe's Peppers $ The sort command arranges lines of text alphabetically by default. There are many options that control the sorting −

More than two commands may be linked up into a pipe. Taking a previous pipe example using grep, we can further sort the files modified in August by the order of size.

The following pipe consists of the commands ls, grep, and sort −

$ls -l | grep "Aug" | sort +4n -rw-rw-r-- 1 carol doc 1605 Aug 23 07:35 macros -rw-rw-r-- 1 john doc 2488 Aug 15 10:51 intro -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 8515 Aug 6 15:30 ch07 -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 11008 Aug 6 14:10 ch02 $ This pipe sorts all files in your directory modified in August by the order of size, and prints them on the terminal screen. The sort option +4n skips four fields (fields are separated by blanks) then sorts the lines in numeric order.

Let's assume that you have a long directory listing. To make it easier to read the sorted listing, pipe the output through more as follows −

$ls -l | grep "Aug" | sort +4n | more -rw-rw-r-- 1 carol doc 1605 Aug 23 07:35 macros -rw-rw-r-- 1 john doc 2488 Aug 15 10:51 intro -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 8515 Aug 6 15:30 ch07 -rw-rw-r-- 1 john doc 14827 Aug 9 12:40 ch03 . . . -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 16867 Aug 6 15:56 ch05 --More--(74%) The screen will fill up once the screen is full of text consisting of lines sorted by the order of the file size. At the bottom of the screen is the more prompt, where you can type a command to move through the sorted text.

Once you're done with this screen, you can use any of the commands listed in the discussion of the more program.

The operating system tracks processes through a five-digit ID number known as the pid or the process ID. Each process in the system has a unique pid.

Pids eventually repeat because all the possible numbers are used up and the next pid rolls or starts over. At any point of time, no two processes with the same pid exist in the system because it is the pid that Unix uses to track each process.

You can see this happen with the ls command. If you wish to list all the files in your current directory, you can use the following command −

While a program is running in the foreground and is time-consuming, no other commands can be run (start any other processes) because the prompt would not be available until the program finishes processing and comes out.

The advantage of running a process in the background is that you can run other commands; you do not have to wait until it completes to start another!

The simplest way to start a background process is to add an ampersand (&) at the end of the command.

That first line contains information about the background process - the job number and the process ID. You need to know the job number to manipulate it between the background and the foreground.

Press the Enter key and you will see the following −

There are other options which can be used along with ps command −

If a process is running in the background, you should get its Job ID using the ps command. After that, you can use the kill command to kill the process as follows −

Most of the commands that you run have the shell as their parent. Check the ps -f example where this command listed both the process ID and the parent process ID.

When a process is killed, a ps listing may still show the process with a Z state. This is a zombie or defunct process. The process is dead and not being used. These processes are different from the orphan processes. They have completed execution but still find an entry in the process table.

A daemon has no controlling terminal. It cannot open /dev/tty. If you do a "ps -ef" and look at the tty field, all daemons will have a ? for the tty.

To be precise, a daemon is a process that runs in the background, usually waiting for something to happen that it is capable of working with. For example, a printer daemon waiting for print commands.

If you have a program that calls for lengthy processing, then it’s worth to make it a daemon and run it in the background.

It is an interactive diagnostic tool that updates frequently and shows information about physical and virtual memory, CPU usage, load averages, and your busy processes.

Here is the simple syntax to run top command and to see the statistics of CPU utilization by different processes −

In addition, a job can consist of multiple processes running in a series or at the same time, in parallel. Using the job ID is easier than tracking individual processes.

The ping command is useful for the following −

The ftp utility has its own set of Unix-like commands. These commands help you perform tasks such as −

The following tables lists out a few important commands −

It should be noted that all the files would be downloaded or uploaded

to or from the current directories. If you want to upload your files in

a particular directory, you need to first change to that directory and

then upload the required files.

Once you login using Telnet, you can perform all the activities on your remotely connected machine. The following is an example of Telnet session −

Finger may be disabled on other systems for security reasons.

Following is the simple syntax to use the finger command −

Check all the logged-in users on the local machine −

vi is generally considered the de facto standard in Unix editors because −

Following is an example to create a new file testfile if it already does not exist in the current working directory −

$vi testfile The above command will generate the following output −

| ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ "testfile" [New File] You will notice a tilde (~) on each line following the cursor. A tilde represents an unused line. If a line does not begin with a tilde and appears to be blank, there is a space, tab, newline, or some other non-viewable character present.

You now have one open file to start working on. Before proceeding further, let us understand a few important concepts.

Hint − If you are not sure which mode you are in, press the Esc key twice; this will take you to the command mode. You open a file using the vi editor. Start by typing some characters and then come to the command mode to understand the difference.

The command to save the contents of the editor is :w. You can combine the above command with the quit command, or use :wq and return.

The easiest way to save your changes and exit vi is with the ZZ command. When you are in the command mode, type ZZ. The ZZ command works the same way as the :wq command.

If you want to specify/state any particular name for the file, you can do so by specifying it after the :w. For example, if you wanted to save the file you were working on as another filename called filename2, you would type :w filename2 and return.

The following points need to be considered to move within a file −

As mentioned above, most commands in vi can be prefaced by the number of times you want the action to occur. For example, 2x deletes two characters under the cursor location and 2dd deletes two lines the cursor is on.

It is recommended that the commands are practiced before we proceed further.

These two commands differ only in the direction where the search takes place −

The character search searches within one line to find a character entered after the command. The f and F commands search for a character on the current line only. f searches forwards and F searches backwards and the cursor moves to the position of the found character.

The t and T commands search for a character on the current line only, but for t, the cursor moves to the position before the character, and T searches the line backwards to the position after the character.

For example, if you want to check whether a file exists before you try to save your file with that filename, you can type :! ls and you will see the output of ls on the screen.

You can press any key (or the command's escape sequence) to return to your vi session.

:s/search/replace/g The g stands for globally. The result of this command is that all occurrences on the cursor's line are changed.

Unix / Linux for Beginners

Unix is a computer Operating System which is capable of handling activities from multiple users at the same time. The development of Unix started around 1969 at AT&T Bell Labs by Ken Thompson

and Dennis Ritchie. This tutorial gives a very good understanding on Unix.

Prerequisites

We assume you have adequate exposure to Operating Systems and their functionalities. A basic understanding on various computer concepts will also help you in understanding the various exercises given in this tutorial.Execute Unix Shell Programs

If you are willing to learn the Unix/Linux basic commands and Shell script but you do not have a setup for the same, then do not worry — The CodingGround is available on a highend dedicated server giving you real programming experience with the comfort of singleclick execution. Yes! It is absolutely free and online.Basics:

Unix is a computer Operating System which is capable of handling activities from multiple users at the same time. The development of Unix started around 1969 at AT&T Bell Labs by Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie. This tutorial gives a very good understanding on Unix.

We assume you have adequate exposure to Operating Systems and their functionalities. A basic understanding on various computer concepts will also help you in understanding the various exercises given in this tutorial.

If you are willing to learn the Unix/Linux basic commands and Shell script but you do not have a setup for the same, then do not worry — The CodingGround is available on a highend dedicated server giving you real programming experience with the comfort of singleclick execution. Yes! It is absolutely free and online.

What is Unix ?

The Unix operating system is a set of programs that act as a link between the computer and the user.The computer programs that allocate the system resources and coordinate all the details of the computer's internals is called the operating system or the kernel.

Users communicate with the kernel through a program known as the shell. The shell is a command line interpreter; it translates commands entered by the user and converts them into a language that is understood by the kernel.

- Unix was originally developed in 1969 by a group of AT&T employees Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, Douglas McIlroy, and Joe Ossanna at Bell Labs.

- There are various Unix variants available in the market. Solaris Unix, AIX, HP Unix and BSD are a few examples. Linux is also a flavor of Unix which is freely available.

- Several people can use a Unix computer at the same time; hence Unix is called a multiuser system.

- A user can also run multiple programs at the same time; hence Unix is a multitasking environment.

Unix Architecture

Here is a basic block diagram of a Unix system − The main concept that unites all the versions of Unix is the following four basics −

The main concept that unites all the versions of Unix is the following four basics −- Kernel − The kernel is the heart of the operating system. It interacts with the hardware and most of the tasks like memory management, task scheduling and file management.

- Shell − The shell is the utility that processes your requests. When you type in a command at your terminal, the shell interprets the command and calls the program that you want. The shell uses standard syntax for all commands. C Shell, Bourne Shell and Korn Shell are the most famous shells which are available with most of the Unix variants.

- Commands and Utilities − There are various commands and utilities which you can make use of in your day to day activities. cp, mv, cat and grep, etc. are few examples of commands and utilities. There are over 250 standard commands plus numerous others provided through 3rd party software. All the commands come along with various options.

- Files and Directories − All the data of Unix is organized into files. All files are then organized into directories. These directories are further organized into a tree-like structure called the filesystem.

System Bootup

If you have a computer which has the Unix operating system installed in it, then you simply need to turn on the system to make it live.As soon as you turn on the system, it starts booting up and finally it prompts you to log into the system, which is an activity to log into the system and use it for your day-to-day activities.

Login Unix

When you first connect to a Unix system, you usually see a prompt such as the following −login:

To log in

- Have your userid (user identification) and password ready. Contact your system administrator if you don't have these yet.

- Type your userid at the login prompt, then press ENTER. Your userid is case-sensitive, so be sure you type it exactly as your system administrator has instructed.

- Type your password at the password prompt, then press ENTER. Your password is also case-sensitive.

- If you provide the correct userid and password, then you will be allowed to enter into the system. Read the information and messages that comes up on the screen, which is as follows.

login : amrood amrood's password: Last login: Sun Jun 14 09:32:32 2009 from 62.61.164.73 $You will be provided with a command prompt (sometime called the $ prompt ) where you type all your commands. For example, to check calendar, you need to type the cal command as follows −

$ cal

June 2009

Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa

1 2 3 4 5 6

7 8 9 10 11 12 13

14 15 16 17 18 19 20

21 22 23 24 25 26 27

28 29 30

$

Change Password

All Unix systems require passwords to help ensure that your files and data remain your own and that the system itself is secure from hackers and crackers. Following are the steps to change your password −Step 1 − To start, type password at the command prompt as shown below.

Step 2 − Enter your old password, the one you're currently using.

Step 3 − Type in your new password. Always keep your password complex enough so that nobody can guess it. But make sure, you remember it.

Step 4 − You must verify the password by typing it again.

$ passwd Changing password for amrood (current) Unix password:****** New UNIX password:******* Retype new UNIX password:******* passwd: all authentication tokens updated successfully $Note − We have added asterisk (*) here just to show the location where you need to enter the current and new passwords otherwise at your system. It does not show you any character when you type.

Listing Directories and Files

All data in Unix is organized into files. All files are organized into directories. These directories are organized into a tree-like structure called the filesystem.You can use the ls command to list out all the files or directories available in a directory. Following is the example of using ls command with -l option.

$ ls -l total 19621 drwxrwxr-x 2 amrood amrood 4096 Dec 25 09:59 uml -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 5341 Dec 25 08:38 uml.jpg drwxr-xr-x 2 amrood amrood 4096 Feb 15 2006 univ drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Dec 9 2007 urlspedia -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 276480 Dec 9 2007 urlspedia.tar drwxr-xr-x 8 root root 4096 Nov 25 2007 usr -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 3192 Nov 25 2007 webthumb.php -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 20480 Nov 25 2007 webthumb.tar -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 5654 Aug 9 2007 yourfile.mid -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 166255 Aug 9 2007 yourfile.swf $Here entries starting with d..... represent directories. For example, uml, univ and urlspedia are directories and rest of the entries are files.

Who Are You?

While you're logged into the system, you might be willing to know : Who am I?The easiest way to find out "who you are" is to enter the whoami command −

$ whoami amrood $Try it on your system. This command lists the account name associated with the current login. You can try who am i command as well to get information about yourself.

Who is Logged in?

Sometime you might be interested to know who is logged in to the computer at the same time.There are three commands available to get you this information, based on how much you wish to know about the other users: users, who, and w.

$ users amrood bablu qadir $ who amrood ttyp0 Oct 8 14:10 (limbo) bablu ttyp2 Oct 4 09:08 (calliope) qadir ttyp4 Oct 8 12:09 (dent) $Try the w command on your system to check the output. This lists down information associated with the users logged in the system.

Logging Out

When you finish your session, you need to log out of the system. This is to ensure that nobody else accesses your files.To log out

- Just type the logout command at the command prompt, and the system will clean up everything and break the connection.

System Shutdown

The most consistent way to shut down a Unix system properly via the command line is to use one of the following commands −| Sr.No. | Command & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | halt Brings the system down immediately |

| 2 | init 0 Powers off the system using predefined scripts to synchronize and clean up the system prior to shutting down |

| 3 | init 6 Reboots the system by shutting it down completely and then restarting it |

| 4 | poweroff Shuts down the system by powering off |

| 5 | reboot Reboots the system |

| 6 | shutdown Shuts down the system |

File Management

In this chapter, we will discuss in detail about file management in Unix. All data in Unix is organized into files. All files are organized into directories. These directories are organized into a tree-like structure called the filesystem.

When you work with Unix, one way or another, you spend most of your time working with files. This tutorial will help you understand how to create and remove files, copy and rename them, create links to them, etc.

In Unix, there are three basic types of files −

- Ordinary Files − An ordinary file is a file on the system that contains data, text, or program instructions. In this tutorial, you look at working with ordinary files.

- Directories − Directories store both special and ordinary files. For users familiar with Windows or Mac OS, Unix directories are equivalent to folders.

- Special Files − Some special files provide access to hardware such as hard drives, CD-ROM drives, modems, and Ethernet adapters. Other special files are similar to aliases or shortcuts and enable you to access a single file using different names.

Listing Files

To list the files and directories stored in the current directory, use the following command −$lsHere is the sample output of the above command −

$ls bin hosts lib res.03 ch07 hw1 pub test_results ch07.bak hw2 res.01 users docs hw3 res.02 workThe command ls supports the -l option which would help you to get more information about the listed files −

$ls -l total 1962188 drwxrwxr-x 2 amrood amrood 4096 Dec 25 09:59 uml -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 5341 Dec 25 08:38 uml.jpg drwxr-xr-x 2 amrood amrood 4096 Feb 15 2006 univ drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Dec 9 2007 urlspedia -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 276480 Dec 9 2007 urlspedia.tar drwxr-xr-x 8 root root 4096 Nov 25 2007 usr drwxr-xr-x 2 200 300 4096 Nov 25 2007 webthumb-1.01 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 3192 Nov 25 2007 webthumb.php -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 20480 Nov 25 2007 webthumb.tar -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 5654 Aug 9 2007 yourfile.mid -rw-rw-r-- 1 amrood amrood 166255 Aug 9 2007 yourfile.swf drwxr-xr-x 11 amrood amrood 4096 May 29 2007 zlib-1.2.3 $Here is the information about all the listed columns −

- First Column − Represents the file type and the permission given on the file. Below is the description of all type of files.

- Second Column − Represents the number of memory blocks taken by the file or directory.

- Third Column − Represents the owner of the file. This is the Unix user who created this file.

- Fourth Column − Represents the group of the owner. Every Unix user will have an associated group.

- Fifth Column − Represents the file size in bytes.

- Sixth Column − Represents the date and the time when this file was created or modified for the last time.

- Seventh Column − Represents the file or the directory name.

| Sr.No. | Prefix & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | - Regular file, such as an ASCII text file, binary executable, or hard link. |

| 2 | b Block special file. Block input/output device file such as a physical hard drive. |

| 3 | c Character special file. Raw input/output device file such as a physical hard drive. |

| 4 | d Directory file that contains a listing of other files and directories. |

| 5 | l Symbolic link file. Links on any regular file. |

| 6 | p Named pipe. A mechanism for interprocess communications. |

| 7 | s Socket used for interprocess communication. |

Metacharacters

Metacharacters have a special meaning in Unix. For example, * and ? are metacharacters. We use * to match 0 or more characters, a question mark (?) matches with a single character.For Example −

$ls ch*.docDisplays all the files, the names of which start with ch and end with .doc −

ch01-1.doc ch010.doc ch02.doc ch03-2.doc ch04-1.doc ch040.doc ch05.doc ch06-2.doc ch01-2.doc ch02-1.doc cHere, * works as meta character which matches with any character. If you want to display all the files ending with just .doc, then you can use the following command −

$ls *.doc

Hidden Files

An invisible file is one, the first character of which is the dot or the period character (.). Unix programs (including the shell) use most of these files to store configuration information.Some common examples of the hidden files include the files −

- .profile − The Bourne shell ( sh) initialization script

- .kshrc − The Korn shell ( ksh) initialization script

- .cshrc − The C shell ( csh) initialization script

- .rhosts − The remote shell configuration file

$ ls -a . .profile docs lib test_results .. .rhosts hosts pub users .emacs bin hw1 res.01 work .exrc ch07 hw2 res.02 .kshrc ch07.bak hw3 res.03 $

- Single dot (.) − This represents the current directory.

- Double dot (..) − This represents the parent directory.

Creating Files

You can use the vi editor to create ordinary files on any Unix system. You simply need to give the following command −$ vi filenameThe above command will open a file with the given filename. Now, press the key i to come into the edit mode. Once you are in the edit mode, you can start writing your content in the file as in the following program −

This is unix file....I created it for the first time..... I'm going to save this content in this file.Once you are done with the program, follow these steps −

- Press the key esc to come out of the edit mode.

- Press two keys Shift + ZZ together to come out of the file completely.

$ vi filename $

Editing Files

You can edit an existing file using the vi editor. We will discuss in short how to open an existing file −$ vi filenameOnce the file is opened, you can come in the edit mode by pressing the key i and then you can proceed by editing the file. If you want to move here and there inside a file, then first you need to come out of the edit mode by pressing the key Esc. After this, you can use the following keys to move inside a file −

- l key to move to the right side.

- h key to move to the left side.

- k key to move upside in the file.

- j key to move downside in the file.

Display Content of a File

You can use the cat command to see the content of a file. Following is a simple example to see the content of the above created file −$ cat filename This is unix file....I created it for the first time..... I'm going to save this content in this file. $You can display the line numbers by using the -b option along with the cat command as follows −

$ cat -b filename 1 This is unix file....I created it for the first time..... 2 I'm going to save this content in this file. $

Counting Words in a File

You can use the wc command to get a count of the total number of lines, words, and characters contained in a file. Following is a simple example to see the information about the file created above −$ wc filename 2 19 103 filename $Here is the detail of all the four columns −

- First Column − Represents the total number of lines in the file.

- Second Column − Represents the total number of words in the file.

- Third Column − Represents the total number of bytes in the file. This is the actual size of the file.

- Fourth Column − Represents the file name.

$ wc filename1 filename2 filename3

Copying Files

To make a copy of a file use the cp command. The basic syntax of the command is −$ cp source_file destination_fileFollowing is the example to create a copy of the existing file filename.

$ cp filename copyfile $You will now find one more file copyfile in your current directory. This file will exactly be the same as the original file filename.

Renaming Files

To change the name of a file, use the mv command. Following is the basic syntax −$ mv old_file new_fileThe following program will rename the existing file filename to newfile.

$ mv filename newfile $The mv command will move the existing file completely into the new file. In this case, you will find only newfile in your current directory.

Deleting Files

To delete an existing file, use the rm command. Following is the basic syntax −$ rm filenameCaution − A file may contain useful information. It is always recommended to be careful while using this Delete command. It is better to use the -i option along with rm command.

Following is the example which shows how to completely remove the existing file filename.

$ rm filename $You can remove multiple files at a time with the command given below −

$ rm filename1 filename2 filename3 $

Standard Unix Streams

Under normal circumstances, every Unix program has three streams (files) opened for it when it starts up −- stdin − This is referred to as the standard input and the associated file descriptor is 0. This is also represented as STDIN. The Unix program will read the default input from STDIN.

- stdout − This is referred to as the standard output and the associated file descriptor is 1. This is also represented as STDOUT. The Unix program will write the default output at STDOUT

- stderr − This is referred to as the standard error

and the associated file descriptor is 2. This is also represented as

STDERR. The Unix program will write all the error messages at STDERR.

Unix / Linux - Directory Management

In this chapter, we will discuss in detail about directory management in Unix. A directory is a file the solo job of which is to store the file names and the related information. All the files, whether ordinary, special, or directory, are contained in directories.

Unix uses a hierarchical structure for organizing files and directories. This structure is often referred to as a directory tree. The tree has a single root node, the slash character (/), and all other directories are contained below it.

Home Directory

The directory in which you find yourself when you first login is called your home directory.

You will be doing much of your work in your home directory and subdirectories that you'll be creating to organize your files.

You can go in your home directory anytime using the following command −

$cd ~ $

Here ~ indicates the home directory. Suppose you have to go in any other user's home directory, use the following command −

$cd ~username $

To go in your last directory, you can use the following command −

$cd - $

Absolute/Relative Pathnames

Directories are arranged in a hierarchy with root (/) at the top. The position of any file within the hierarchy is described by its pathname.

Elements of a pathname are separated by a /. A pathname is absolute, if it is described in relation to root, thus absolute pathnames always begin with a /.

Following are some examples of absolute filenames.

/etc/passwd /users/sjones/chem/notes /dev/rdsk/Os3

A pathname can also be relative to your current working directory. Relative pathnames never begin with /. Relative to user amrood's home directory, some pathnames might look like this −

chem/notes personal/res

To determine where you are within the filesystem hierarchy at any time, enter the command pwd to print the current working directory −

$pwd /user0/home/amrood $

Listing Directories

To list the files in a directory, you can use the following syntax −

$ls dirname

Following is the example to list all the files contained in /usr/local directory −

$ls /usr/local X11 bin gimp jikes sbin ace doc include lib share atalk etc info man ami

Creating Directories

We will now understand how to create directories. Directories are created by the following command −

$mkdir dirname

Here, directory is the absolute or relative pathname of the directory you want to create. For example, the command −

$mkdir mydir $

Creates the directory mydir in the current directory. Here is another example −

$mkdir /tmp/test-dir $

This command creates the directory test-dir in the /tmp directory. The mkdir command produces no output if it successfully creates the requested directory.

If you give more than one directory on the command line, mkdir creates each of the directories. For example, −

$mkdir docs pub $

Creates the directories docs and pub under the current directory.

Creating Parent Directories

We will now understand how to create parent directories. Sometimes when you want to create a directory, its parent directory or directories might not exist. In this case, mkdir issues an error message as follows −

$mkdir /tmp/amrood/test mkdir: Failed to make directory "/tmp/amrood/test"; No such file or directory $

In such cases, you can specify the -p option to the mkdir command. It creates all the necessary directories for you. For example −

$mkdir -p /tmp/amrood/test $

The above command creates all the required parent directories.

Removing Directories

Directories can be deleted using the rmdir command as follows −

$rmdir dirname $

Note − To remove a directory, make sure it is empty which means there should not be any file or sub-directory inside this directory.

You can remove multiple directories at a time as follows −

$rmdir dirname1 dirname2 dirname3 $

The above command removes the directories dirname1, dirname2, and dirname3, if they are empty. The rmdir command produces no output if it is successful.

Changing Directories

You can use the cd command to do more than just change to a home directory. You can use it to change to any directory by specifying a valid absolute or relative path. The syntax is as given below −

$cd dirname $

Here, dirname is the name of the directory that you want to change to. For example, the command −

$cd /usr/local/bin $

Changes to the directory /usr/local/bin. From this directory, you can cd to the directory /usr/home/amrood using the following relative path −

$cd ../../home/amrood $

Renaming Directories

The mv (move) command can also be used to rename a directory. The syntax is as follows −

$mv olddir newdir $

You can rename a directory mydir to yourdir as follows −

$mv mydir yourdir $

The directories . (dot) and .. (dot dot)

The filename . (dot) represents the current working directory; and the filename .. (dot dot) represents the directory one level above the current working directory, often referred to as the parent directory.

If we enter the command to show a listing of the current working directories/files and use the -a option to list all the files and the -l option to provide the long listing, we will receive the following result.

$ls -la drwxrwxr-x 4 teacher class 2048 Jul 16 17.56 . drwxr-xr-x 60 root 1536 Jul 13 14:18 .. ---------- 1 teacher class 4210 May 1 08:27 .profile -rwxr-xr-x 1 teacher class 1948 May 12 13:42 memo $

Unix / Linux - File Permission / Access Modes

In this chapter, we will discuss in detail about file permission and access modes in Unix. File ownership is an important component of Unix that provides a secure method for storing files. Every file in Unix has the following attributes − - Owner permissions − The owner's permissions determine what actions the owner of the file can perform on the file.

- Group permissions − The group's permissions determine what actions a user, who is a member of the group that a file belongs to, can perform on the file.

- Other (world) permissions − The permissions for others indicate what action all other users can perform on the file.

The Permission Indicators

While using ls -l command, it displays various information related to file permission as follows −$ls -l /home/amrood -rwxr-xr-- 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 myfile drwxr-xr--- 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 mydirHere, the first column represents different access modes, i.e., the permission associated with a file or a directory.

The permissions are broken into groups of threes, and each position in the group denotes a specific permission, in this order: read (r), write (w), execute (x) −

- The first three characters (2-4) represent the permissions for the file's owner. For example, -rwxr-xr-- represents that the owner has read (r), write (w) and execute (x) permission.

- The second group of three characters (5-7) consists of the permissions for the group to which the file belongs. For example, -rwxr-xr-- represents that the group has read (r) and execute (x) permission, but no write permission.

- The last group of three characters (8-10) represents the permissions for everyone else. For example, -rwxr-xr-- represents that there is read (r) only permission.

File Access Modes

The permissions of a file are the first line of defense in the security of a Unix system. The basic building blocks of Unix permissions are the read, write, and execute permissions, which have been described below −Read

Grants the capability to read, i.e., view the contents of the file.Write

Grants the capability to modify, or remove the content of the file.Execute

User with execute permissions can run a file as a program.Directory Access Modes

Directory access modes are listed and organized in the same manner as any other file. There are a few differences that need to be mentioned −Read

Access to a directory means that the user can read the contents. The user can look at the filenames inside the directory.Write

Access means that the user can add or delete files from the directory.Execute

Executing a directory doesn't really make sense, so think of this as a traverse permission.A user must have execute access to the bin directory in order to execute the ls or the cd command.

Changing Permissions

To change the file or the directory permissions, you use the chmod (change mode) command. There are two ways to use chmod — the symbolic mode and the absolute mode.Using chmod in Symbolic Mode

The easiest way for a beginner to modify file or directory permissions is to use the symbolic mode. With symbolic permissions you can add, delete, or specify the permission set you want by using the operators in the following table.| Sr.No. | Chmod operator & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | + Adds the designated permission(s) to a file or directory. |

| 2 | - Removes the designated permission(s) from a file or directory. |

| 3 | = Sets the designated permission(s). |

$ls -l testfile -rwxrwxr-- 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfileThen each example chmod command from the preceding table is run on the testfile, followed by ls –l, so you can see the permission changes −

$chmod o+wx testfile $ls -l testfile -rwxrwxrwx 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfile $chmod u-x testfile $ls -l testfile -rw-rwxrwx 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfile $chmod g = rx testfile $ls -l testfile -rw-r-xrwx 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfileHere's how you can combine these commands on a single line −

$chmod o+wx,u-x,g = rx testfile $ls -l testfile -rw-r-xrwx 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfile

Using chmod with Absolute Permissions

The second way to modify permissions with the chmod command is to use a number to specify each set of permissions for the file.Each permission is assigned a value, as the following table shows, and the total of each set of permissions provides a number for that set.

| Number | Octal Permission Representation | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | No permission | --- |

| 1 | Execute permission | --x |

| 2 | Write permission | -w- |

| 3 | Execute and write permission: 1 (execute) + 2 (write) = 3 | -wx |

| 4 | Read permission | r-- |

| 5 | Read and execute permission: 4 (read) + 1 (execute) = 5 | r-x |

| 6 | Read and write permission: 4 (read) + 2 (write) = 6 | rw- |

| 7 | All permissions: 4 (read) + 2 (write) + 1 (execute) = 7 | rwx |

$ls -l testfile -rwxrwxr-- 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfileThen each example chmod command from the preceding table is run on the testfile, followed by ls –l, so you can see the permission changes −

$ chmod 755 testfile $ls -l testfile -rwxr-xr-x 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfile $chmod 743 testfile $ls -l testfile -rwxr---wx 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfile $chmod 043 testfile $ls -l testfile ----r---wx 1 amrood users 1024 Nov 2 00:10 testfile

Changing Owners and Groups

While creating an account on Unix, it assigns a owner ID and a group ID to each user. All the permissions mentioned above are also assigned based on the Owner and the Groups.Two commands are available to change the owner and the group of files −

- chown − The chown command stands for "change owner" and is used to change the owner of a file.

- chgrp − The chgrp command stands for "change group" and is used to change the group of a file.

Changing Ownership

The chown command changes the ownership of a file. The basic syntax is as follows −$ chown user filelistThe value of the user can be either the name of a user on the system or the user id (uid) of a user on the system.

The following example will help you understand the concept −

$ chown amrood testfile $Changes the owner of the given file to the user amrood.

NOTE − The super user, root, has the unrestricted capability to change the ownership of any file but normal users can change the ownership of only those files that they own.

Changing Group Ownership

The chgrp command changes the group ownership of a file. The basic syntax is as follows −$ chgrp group filelistThe value of group can be the name of a group on the system or the group ID (GID) of a group on the system.

Following example helps you understand the concept −

$ chgrp special testfile $Changes the group of the given file to special group.

SUID and SGID File Permission

Often when a command is executed, it will have to be executed with special privileges in order to accomplish its task.As an example, when you change your password with the passwd command, your new password is stored in the file /etc/shadow.

As a regular user, you do not have read or write access to this file for security reasons, but when you change your password, you need to have the write permission to this file. This means that the passwd program has to give you additional permissions so that you can write to the file /etc/shadow.

Additional permissions are given to programs via a mechanism known as the Set User ID (SUID) and Set Group ID (SGID) bits.

When you execute a program that has the SUID bit enabled, you inherit the permissions of that program's owner. Programs that do not have the SUID bit set are run with the permissions of the user who started the program.

This is the case with SGID as well. Normally, programs execute with your group permissions, but instead your group will be changed just for this program to the group owner of the program.

The SUID and SGID bits will appear as the letter "s" if the permission is available. The SUID "s" bit will be located in the permission bits where the owners’ execute permission normally resides.

For example, the command −

$ ls -l /usr/bin/passwd -r-sr-xr-x 1 root bin 19031 Feb 7 13:47 /usr/bin/passwd* $Shows that the SUID bit is set and that the command is owned by the root. A capital letter S in the execute position instead of a lowercase s indicates that the execute bit is not set.

If the sticky bit is enabled on the directory, files can only be removed if you are one of the following users −

- The owner of the sticky directory

- The owner of the file being removed

- The super user, root

$ chmod ug+s dirname $ ls -l drwsr-sr-x 2 root root 4096 Jun 19 06:45 dirname $

Unix / Linux - Environment

In this chapter, we will discuss in detail about the Unix environment. An important Unix concept is the environment, which is defined by environment variables. Some are set by the system, others by you, yet others by the shell, or any program that loads another program. A variable is a character string to which we assign a value. The value assigned could be a number, text, filename, device, or any other type of data.For example, first we set a variable TEST and then we access its value using the echo command −

$TEST="Unix Programming" $echo $TEST It produces the following result.

Unix Programming Note that the environment variables are set without using the $ sign but while accessing them we use the $ sign as prefix. These variables retain their values until we come out of the shell.

When you log in to the system, the shell undergoes a phase called initialization to set up the environment. This is usually a two-step process that involves the shell reading the following files −

- /etc/profile

- profile

- The shell checks to see whether the file /etc/profile exists.

- If it exists, the shell reads it. Otherwise, this file is skipped. No error message is displayed.

- The shell checks to see whether the file .profile exists in your home directory. Your home directory is the directory that you start out in after you log in.

- If it exists, the shell reads it; otherwise, the shell skips it. No error message is displayed.

$ This is the prompt where you can enter commands in order to have them executed.

Note − The shell initialization process detailed here applies to all Bourne type shells, but some additional files are used by bash and ksh.

The .profile File

The file /etc/profile is maintained by the system administrator of your Unix machine and contains shell initialization information required by all users on a system.The file .profile is under your control. You can add as much shell customization information as you want to this file. The minimum set of information that you need to configure includes −

- The type of terminal you are using.

- A list of directories in which to locate the commands.

- A list of variables affecting the look and feel of your terminal.

Setting the Terminal Type

Usually, the type of terminal you are using is automatically configured by either the login or getty programs. Sometimes, the auto configuration process guesses your terminal incorrectly.If your terminal is set incorrectly, the output of the commands might look strange, or you might not be able to interact with the shell properly.

To make sure that this is not the case, most users set their terminal to the lowest common denominator in the following way −

$TERM=vt100 $

Setting the PATH

When you type any command on the command prompt, the shell has to locate the command before it can be executed.The PATH variable specifies the locations in which the shell should look for commands. Usually the Path variable is set as follows −

$PATH=/bin:/usr/bin $ Here, each of the individual entries separated by the colon character (:) are directories. If you request the shell to execute a command and it cannot find it in any of the directories given in the PATH variable, a message similar to the following appears −

$hello hello: not found $ There are variables like PS1 and PS2 which are discussed in the next section.

PS1 and PS2 Variables

The characters that the shell displays as your command prompt are stored in the variable PS1. You can change this variable to be anything you want. As soon as you change it, it'll be used by the shell from that point on.For example, if you issued the command −

$PS1='=>' => => => Your prompt will become =>. To set the value of PS1 so that it shows the working directory, issue the command −

=>PS1="[\u@\h \w]\$" [root@ip-72-167-112-17 /var/www/tutorialspoint/unix]$ [root@ip-72-167-112-17 /var/www/tutorialspoint/unix]$ The result of this command is that the prompt displays the user's username, the machine's name (hostname), and the working directory.

There are quite a few escape sequences that can be used as value arguments for PS1; try to limit yourself to the most critical so that the prompt does not overwhelm you with information.

| Sr.No. | Escape Sequence & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | \t Current time, expressed as HH:MM:SS |

| 2 | \d Current date, expressed as Weekday Month Date |

| 3 | \n Newline |

| 4 | \s Current shell environment |

| 5 | \W Working directory |

| 6 | \w Full path of the working directory |

| 7 | \u Current user’s username |

| 8 | \h Hostname of the current machine |

| 9 | \# Command number of the current command. Increases when a new command is entered |

| 10 | \$ If the effective UID is 0 (that is, if you are logged in as root), end the prompt with the # character; otherwise, use the $ sign |

When you issue a command that is incomplete, the shell will display a secondary prompt and wait for you to complete the command and hit Enter again.

The default secondary prompt is > (the greater than sign), but can be changed by re-defining the PS2 shell variable −

Following is the example which uses the default secondary prompt −

$ echo "this is a > test" this is a test $ The example given below re-defines PS2 with a customized prompt −

$ PS2="secondary prompt->" $ echo "this is a secondary prompt->test" this is a test $

Environment Variables

Following is the partial list of important environment variables. These variables are set and accessed as mentioned below −| Sr.No. | Variable & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | DISPLAY Contains the identifier for the display that X11 programs should use by default. |

| 2 | HOME Indicates the home directory of the current user: the default argument for the cd built-in command. |

| 3 | IFS Indicates the Internal Field Separator that is used by the parser for word splitting after expansion. |

| 4 | LANG LANG expands to the default system locale; LC_ALL can be used to override this. For example, if its value is pt_BR, then the language is set to (Brazilian) Portuguese and the locale to Brazil. |

| 5 | LD_LIBRARY_PATH A Unix system with a dynamic linker, contains a colonseparated list of directories that the dynamic linker should search for shared objects when building a process image after exec, before searching in any other directories. |

| 6 | PATH Indicates the search path for commands. It is a colon-separated list of directories in which the shell looks for commands. |

| 7 | PWD Indicates the current working directory as set by the cd command. |

| 8 | RANDOM Generates a random integer between 0 and 32,767 each time it is referenced. |

| 9 | SHLVL Increments by one each time an instance of bash is started. This variable is useful for determining whether the built-in exit command ends the current session. |

| 10 | TERM Refers to the display type. |

| 11 | TZ Refers to Time zone. It can take values like GMT, AST, etc. |

| 12 | UID Expands to the numeric user ID of the current user, initialized at the shell startup. |

$ echo $HOME /root ]$ echo $DISPLAY $ echo $TERM xterm $ echo $PATH /usr/local/bin:/bin:/usr/bin:/home/amrood/bin:/usr/local/bin $

Unix / Linux Basic Utilities - Printing, Email

In this chapter, we will discuss in detail about Printing and Email as the basic utilities of Unix. So far, we have tried to understand the Unix OS and the nature of its basic commands. In this chapter, we will learn some important Unix utilities that can be used in our day-to-day life.Printing Files

Before you print a file on a Unix system, you may want to reformat it to adjust the margins, highlight some words, and so on. Most files can also be printed without reformatting, but the raw printout may not be that appealing.Many versions of Unix include two powerful text formatters, nroff and troff.

The pr Command

The pr command does minor formatting of files on the terminal screen or for a printer. For example, if you have a long list of names in a file, you can format it onscreen into two or more columns.Following is the syntax for the pr command −

pr option(s) filename(s)The pr changes the format of the file only on the screen or on the printed copy; it doesn't modify the original file. Following table lists some pr options −

| Sr.No. | Option & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | -k Produces k columns of output |

| 2 | -d Double-spaces the output (not on all pr versions) |

| 3 | -h "header" Takes the next item as a report header |

| 4 | -t Eliminates the printing of header and the top/bottom margins |

| 5 | -l PAGE_LENGTH Sets the page length to PAGE_LENGTH (66) lines. The default number of lines of text is 56 |

| 6 | -o MARGIN Offsets each line with MARGIN (zero) spaces |

| 7 | -w PAGE_WIDTH Sets the page width to PAGE_WIDTH (72) characters for multiple text-column output only |

$cat food Sweet Tooth Bangkok Wok Mandalay Afghani Cuisine Isle of Java Big Apple Deli Sushi and Sashimi Tio Pepe's Peppers ........ $Let's use the pr command to make a two-column report with the header Restaurants −

$pr -2 -h "Restaurants" food Nov 7 9:58 1997 Restaurants Page 1 Sweet Tooth Isle of Java Bangkok Wok Big Apple Deli Mandalay Sushi and Sashimi Afghani Cuisine Tio Pepe's Peppers ........ $

The lp and lpr Commands

The command lp or lpr prints a file onto paper as opposed to the screen display. Once you are ready with formatting using the pr command, you can use any of these commands to print your file on the printer connected to your computer.Your system administrator has probably set up a default printer at your site. To print a file named food on the default printer, use the lp or lpr command, as in the following example −

$lp food request id is laserp-525 (1 file) $The lp command shows an ID that you can use to cancel the print job or check its status.

- If you are using the lp command, you can use the -nNum option to print Num number of copies. Along with the command lpr, you can use -Num for the same.

- If there are multiple printers connected with the shared network, then you can choose a printer using -dprinter option along with lp command and for the same purpose you can use -Pprinter option along with lpr command. Here printer is the printer name.

The lpstat and lpq Commands

The lpstat command shows what's in the printer queue: request IDs, owners, file sizes, when the jobs were sent for printing, and the status of the requests.Use lpstat -o if you want to see all output requests other than just your own. Requests are shown in the order they'll be printed −

$lpstat -o laserp-573 john 128865 Nov 7 11:27 on laserp laserp-574 grace 82744 Nov 7 11:28 laserp-575 john 23347 Nov 7 11:35 $The lpq gives slightly different information than lpstat -o −

$lpq laserp is ready and printing Rank Owner Job Files Total Size active john 573 report.ps 128865 bytes 1st grace 574 ch03.ps ch04.ps 82744 bytes 2nd john 575 standard input 23347 bytes $Here the first line displays the printer status. If the printer is disabled or running out of paper, you may see different messages on this first line.

The cancel and lprm Commands

The cancel command terminates a printing request from the lp command. The lprm command terminates all lpr requests. You can specify either the ID of the request (displayed by lp or lpq) or the name of the printer.$cancel laserp-575 request "laserp-575" cancelled $To cancel whatever request is currently printing, regardless of its ID, simply enter cancel and the printer name −

$cancel laserp request "laserp-573" cancelled $The lprm command will cancel the active job if it belongs to you. Otherwise, you can give job numbers as arguments, or use a dash (-) to remove all of your jobs −

$lprm 575 dfA575diamond dequeued cfA575diamond dequeued $The lprm command tells you the actual filenames removed from the printer queue.

Sending Email

You use the Unix mail command to send and receive mail. Here is the syntax to send an email −$mail [-s subject] [-c cc-addr] [-b bcc-addr] to-addrHere are important options related to mail command −s

| Sr.No. | Option & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | -s Specifies subject on the command line. |

| 2 | -c Sends carbon copies to the list of users. List should be a commaseparated list of names. |

| 3 | -b Sends blind carbon copies to list. List should be a commaseparated list of names. |

$mail -s "Test Message" admin@yahoo.comYou are then expected to type in your message, followed by "control-D" at the beginning of a line. To stop, simply type dot (.) as follows −

Hi, This is a test . Cc:You can send a complete file using a redirect < operator as follows −

$mail -s "Report 05/06/07" admin@yahoo.com < demo.txtTo check incoming email at your Unix system, you simply type email as follows −

$mail no email

Unix / Linux - Pipes and Filters

In this chapter, we will discuss in detail about pipes and filters in Unix. You can connect two commands together so that the output from one program becomes the input of the next program. Two or more commands connected in this way form a pipe. To make a pipe, put a vertical bar (|) on the command line between two commands.When a program takes its input from another program, it performs some operation on that input, and writes the result to the standard output. It is referred to as a filter.

The grep Command

The grep command searches a file or files for lines that have a certain pattern. The syntax is −$grep pattern file(s) The name "grep" comes from the ed (a Unix line editor) command g/re/p which means “globally search for a regular expression and print all lines containing it”.

A regular expression is either some plain text (a word, for example) and/or special characters used for pattern matching.

The simplest use of grep is to look for a pattern consisting of a single word. It can be used in a pipe so that only those lines of the input files containing a given string are sent to the standard output. If you don't give grep a filename to read, it reads its standard input; that's the way all filter programs work −

$ls -l | grep "Aug" -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 11008 Aug 6 14:10 ch02 -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 8515 Aug 6 15:30 ch07 -rw-rw-r-- 1 john doc 2488 Aug 15 10:51 intro -rw-rw-r-- 1 carol doc 1605 Aug 23 07:35 macros $ There are various options which you can use along with the grep command −

| Sr.No. | Option & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | -v Prints all lines that do not match pattern. |

| 2 | -n Prints the matched line and its line number. |

| 3 | -l Prints only the names of files with matching lines (letter "l") |

| 4 | -c Prints only the count of matching lines. |

| 5 | -i Matches either upper or lowercase. |

Here, we are using the -i option to have case insensitive search −

$ls -l | grep -i "carol.*aug" -rw-rw-r-- 1 carol doc 1605 Aug 23 07:35 macros $

The sort Command

The sort command arranges lines of text alphabetically or numerically. The following example sorts the lines in the food file −$sort food Afghani Cuisine Bangkok Wok Big Apple Deli Isle of Java Mandalay Sushi and Sashimi Sweet Tooth Tio Pepe's Peppers $ The sort command arranges lines of text alphabetically by default. There are many options that control the sorting −

| Sr.No. | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | -n Sorts numerically (example: 10 will sort after 2), ignores blanks and tabs. |

| 2 | -r Reverses the order of sort. |

| 3 | -f Sorts upper and lowercase together. |

| 4 | +x Ignores first x fields when sorting. |

The following pipe consists of the commands ls, grep, and sort −

$ls -l | grep "Aug" | sort +4n -rw-rw-r-- 1 carol doc 1605 Aug 23 07:35 macros -rw-rw-r-- 1 john doc 2488 Aug 15 10:51 intro -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 8515 Aug 6 15:30 ch07 -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 11008 Aug 6 14:10 ch02 $ This pipe sorts all files in your directory modified in August by the order of size, and prints them on the terminal screen. The sort option +4n skips four fields (fields are separated by blanks) then sorts the lines in numeric order.

The pg and more Commands

A long output can normally be zipped by you on the screen, but if you run text through more or use the pg command as a filter; the display stops once the screen is full of text.Let's assume that you have a long directory listing. To make it easier to read the sorted listing, pipe the output through more as follows −

$ls -l | grep "Aug" | sort +4n | more -rw-rw-r-- 1 carol doc 1605 Aug 23 07:35 macros -rw-rw-r-- 1 john doc 2488 Aug 15 10:51 intro -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 8515 Aug 6 15:30 ch07 -rw-rw-r-- 1 john doc 14827 Aug 9 12:40 ch03 . . . -rw-rw-rw- 1 john doc 16867 Aug 6 15:56 ch05 --More--(74%) The screen will fill up once the screen is full of text consisting of lines sorted by the order of the file size. At the bottom of the screen is the more prompt, where you can type a command to move through the sorted text.

Once you're done with this screen, you can use any of the commands listed in the discussion of the more program.

Unix / Linux - Processes Management

In this chapter, we will discuss in detail about process management in Unix. When you execute a program on your Unix system, the system creates a special environment for that program. This environment contains everything needed for the system to run the program as if no other program were running on the system. Whenever you issue a command in Unix, it creates, or starts, a new process. When you tried out the ls command to list the directory contents, you started a process. A process, in simple terms, is an instance of a running program.The operating system tracks processes through a five-digit ID number known as the pid or the process ID. Each process in the system has a unique pid.

Pids eventually repeat because all the possible numbers are used up and the next pid rolls or starts over. At any point of time, no two processes with the same pid exist in the system because it is the pid that Unix uses to track each process.

Starting a Process

When you start a process (run a command), there are two ways you can run it −- Foreground Processes

- Background Processes

Foreground Processes

By default, every process that you start runs in the foreground. It gets its input from the keyboard and sends its output to the screen.You can see this happen with the ls command. If you wish to list all the files in your current directory, you can use the following command −

$ls ch*.docThis would display all the files, the names of which start with ch and end with .doc −

ch01-1.doc ch010.doc ch02.doc ch03-2.doc ch04-1.doc ch040.doc ch05.doc ch06-2.doc ch01-2.doc ch02-1.docThe process runs in the foreground, the output is directed to my screen, and if the ls command wants any input (which it does not), it waits for it from the keyboard.

While a program is running in the foreground and is time-consuming, no other commands can be run (start any other processes) because the prompt would not be available until the program finishes processing and comes out.

Background Processes

A background process runs without being connected to your keyboard. If the background process requires any keyboard input, it waits.The advantage of running a process in the background is that you can run other commands; you do not have to wait until it completes to start another!

The simplest way to start a background process is to add an ampersand (&) at the end of the command.

$ls ch*.doc &This displays all those files the names of which start with ch and end with .doc −

ch01-1.doc ch010.doc ch02.doc ch03-2.doc ch04-1.doc ch040.doc ch05.doc ch06-2.doc ch01-2.doc ch02-1.docHere, if the ls command wants any input (which it does not), it goes into a stop state until we move it into the foreground and give it the data from the keyboard.

That first line contains information about the background process - the job number and the process ID. You need to know the job number to manipulate it between the background and the foreground.

Press the Enter key and you will see the following −

[1] + Done ls ch*.doc & $The first line tells you that the ls command background process finishes successfully. The second is a prompt for another command.

Listing Running Processes

It is easy to see your own processes by running the ps (process status) command as follows −$ps PID TTY TIME CMD 18358 ttyp3 00:00:00 sh 18361 ttyp3 00:01:31 abiword 18789 ttyp3 00:00:00 psOne of the most commonly used flags for ps is the -f ( f for full) option, which provides more information as shown in the following example −

$ps -f UID PID PPID C STIME TTY TIME CMD amrood 6738 3662 0 10:23:03 pts/6 0:00 first_one amrood 6739 3662 0 10:22:54 pts/6 0:00 second_one amrood 3662 3657 0 08:10:53 pts/6 0:00 -ksh amrood 6892 3662 4 10:51:50 pts/6 0:00 ps -fHere is the description of all the fields displayed by ps -f command −

| Sr.No. | Column & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | UID User ID that this process belongs to (the person running it) |

| 2 | PID Process ID |

| 3 | PPID Parent process ID (the ID of the process that started it) |

| 4 | C CPU utilization of process |

| 5 | STIME Process start time |

| 6 | TTY Terminal type associated with the process |

| 7 | TIME CPU time taken by the process |

| 8 | CMD The command that started this process |

| Sr.No. | Option & Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | -a Shows information about all users |

| 2 | -x Shows information about processes without terminals |

| 3 | -u Shows additional information like -f option |

| 4 | -e Displays extended information |

Stopping Processes

Ending a process can be done in several different ways. Often, from a console-based command, sending a CTRL + C keystroke (the default interrupt character) will exit the command. This works when the process is running in the foreground mode.If a process is running in the background, you should get its Job ID using the ps command. After that, you can use the kill command to kill the process as follows −

$ps -f UID PID PPID C STIME TTY TIME CMD amrood 6738 3662 0 10:23:03 pts/6 0:00 first_one amrood 6739 3662 0 10:22:54 pts/6 0:00 second_one amrood 3662 3657 0 08:10:53 pts/6 0:00 -ksh amrood 6892 3662 4 10:51:50 pts/6 0:00 ps -f $kill 6738 TerminatedHere, the kill command terminates the first_one process. If a process ignores a regular kill command, you can use kill -9 followed by the process ID as follows −

$kill -9 6738 Terminated

Parent and Child Processes

Each unix process has two ID numbers assigned to it: The Process ID (pid) and the Parent process ID (ppid). Each user process in the system has a parent process.Most of the commands that you run have the shell as their parent. Check the ps -f example where this command listed both the process ID and the parent process ID.

Zombie and Orphan Processes

Normally, when a child process is killed, the parent process is updated via a SIGCHLD signal. Then the parent can do some other task or restart a new child as needed. However, sometimes the parent process is killed before its child is killed. In this case, the "parent of all processes," the init process, becomes the new PPID (parent process ID). In some cases, these processes are called orphan processes.When a process is killed, a ps listing may still show the process with a Z state. This is a zombie or defunct process. The process is dead and not being used. These processes are different from the orphan processes. They have completed execution but still find an entry in the process table.

Daemon Processes

Daemons are system-related background processes that often run with the permissions of root and services requests from other processes.A daemon has no controlling terminal. It cannot open /dev/tty. If you do a "ps -ef" and look at the tty field, all daemons will have a ? for the tty.

To be precise, a daemon is a process that runs in the background, usually waiting for something to happen that it is capable of working with. For example, a printer daemon waiting for print commands.

If you have a program that calls for lengthy processing, then it’s worth to make it a daemon and run it in the background.

The top Command

The top command is a very useful tool for quickly showing processes sorted by various criteria.It is an interactive diagnostic tool that updates frequently and shows information about physical and virtual memory, CPU usage, load averages, and your busy processes.

Here is the simple syntax to run top command and to see the statistics of CPU utilization by different processes −

$top

Job ID Versus Process ID

Background and suspended processes are usually manipulated via job number (job ID). This number is different from the process ID and is used because it is shorter.In addition, a job can consist of multiple processes running in a series or at the same time, in parallel. Using the job ID is easier than tracking individual processes.

Unix / Linux - Network Communication Utilities

In this chapter, we will discuss in detail about network communication utilities in Unix. When you work in a distributed environment, you need to communicate with remote users and you also need to access remote Unix machines. There are several Unix utilities that help users compute in a networked, distributed environment. This chapter lists a few of them.The ping Utility